December, 2021

now browsing by month

10 tips for working with students with disabilities by a veteran teacher

Dr. Jessica Kirker teaches Grades 9-12 at Norristown Area High School in the Norristown Area School District. Jessica serves as the Secondary Division Director for PAEA and is an advocate for every student.

10 tips for working with students with disabilities by a veteran teacher

When I sign IEP documents, I do so under the section listed for “Regular Education Teacher.”

Regular? It doesn’t feel that way. As an art teacher of many students with various disabilities, I don’t feel that my classroom is catering to the “regular.” My frequent discomfort with the term allows me the opportunity to pause and consider what type of education I actually do offer.

Art class has the potential to be the space where EVERY student can find success. However, this takes careful attention to curriculum, facilities, IEPs/504s, adaptations, classroom/school culture, and each individual student’s physical, emotional, and intellectual needs. If it seems overwhelming to think of all of these things at the same time; don’t. Instead, I offer the following list of “10 tips for working with students with disabilities by a veteran teacher” to break some of the larger challenges down into manageable concepts. The following list is for new teachers to begin to build their understanding of all the nuanced components of teaching art to students with disabilities. For the veteran teachers, I offer this list as a chance to have your own moment to pause, reconsider, and possibly revitalize your practice.

- Evaluate your space

There is a natural tendency for art classrooms to be visually “busy” or even downright cluttered. In many cases, a busy art room is a productive art room. There are often multiple materials out and accessible to students. The walls are often bright, lively, and filled with student work. Bright, colorful posters bring a vibrant energy that can excite and inspire. However, the art room can also be overwhelming and overstimulating for some students.

I used to prefer a colorful, busy room. I tried to hang as many posters as my walls would allow and murals filled the spaces void of cork boards. Even the ceiling tiles were painted! However, as I became more in tune with practices that promote mindfulness, the overstimulating art room felt chaotic and wild. Little by little, the posters were reduced. Over the summer the ceiling tiles were replaced and I requested that walls have a fresh coat of paint that would cover the colorful murals.

The new, calmer feel of the art room has been noticed by everyone. Within a month, the classroom had earned the nickname “The Zen Zone.” The walls still have some posters, but the visual clutter has been drastically reduced. I spend much more time at the end of the day putting away all materials that don’t need to be out on countertops to keep the space clutter-free. Jazz or classical music is almost always playing in the background. Finally, the $20 essential oil diffuser that I bought online has been the single best investment of my teaching career.

Changing the learning environment in terms of physical space was a challenging task that required serious reflection as well as calling in for some serious favors (thanks, maintenance department!) However, the payoff was well worth it. The energy of the classroom has shifted and the space is now more welcoming for all students.

- Collaborate with other teachers

This may seem like pretty shallow advice. If you are part of PAEA, you already understand the value of networking and collaboration. However, working with students with disabilities requires a very focused lens when it comes to collaboration.

-Collaborate with your students’ teachers: I will never advocate for the art teacher simply serving as a supplement to “core classes.” When you collaborate with other teachers in your school, make it apparent that it is a reciprocal relationship. Great learning happens when connections are made across disciplines. Inform other teachers of your learning objectives and see how they can welcome multi-modality learning into their classrooms.

– Collaborate with other teachers of students with disabilities: Perhaps sometimes it feels like you are the only one working through these unique challenges, but there are plenty of art teachers out there with classes similar to yours! Even if you are not certified in Special Education, seek out conferences on Disability Studies and connect with teachers whose students’ needs are related to what you experience in your own classroom.

- Don’t assume!

“Those kids can’t….” are the most damaging words I’ve heard in relation to my students with disabilities. It’s easy to focus on the challenges with disabilities and it takes constant reflection to keep your assumptions in check. In the times that I step out of my own comfort level, the students in my Life Skills class never cease to amaze me.

Last month, I led the students in a hand-over-hand wheel throwing activity. My biases and assumptions made me very nervous to attempt this. Some of the students don’t like having dirty hands, so surely this had the potential to go very poorly.

I was remarkably wrong. The smoothness of centered clay proved to be incredibly enjoyable for the students and some of them wouldn’t leave the wheel while others giggled with delight.

Never, ever stop yourself from trying something new or trying something that you think is too hard, too messy, or too challenging. Continue to push your own limits and biases to see some magical things happen in your classroom.

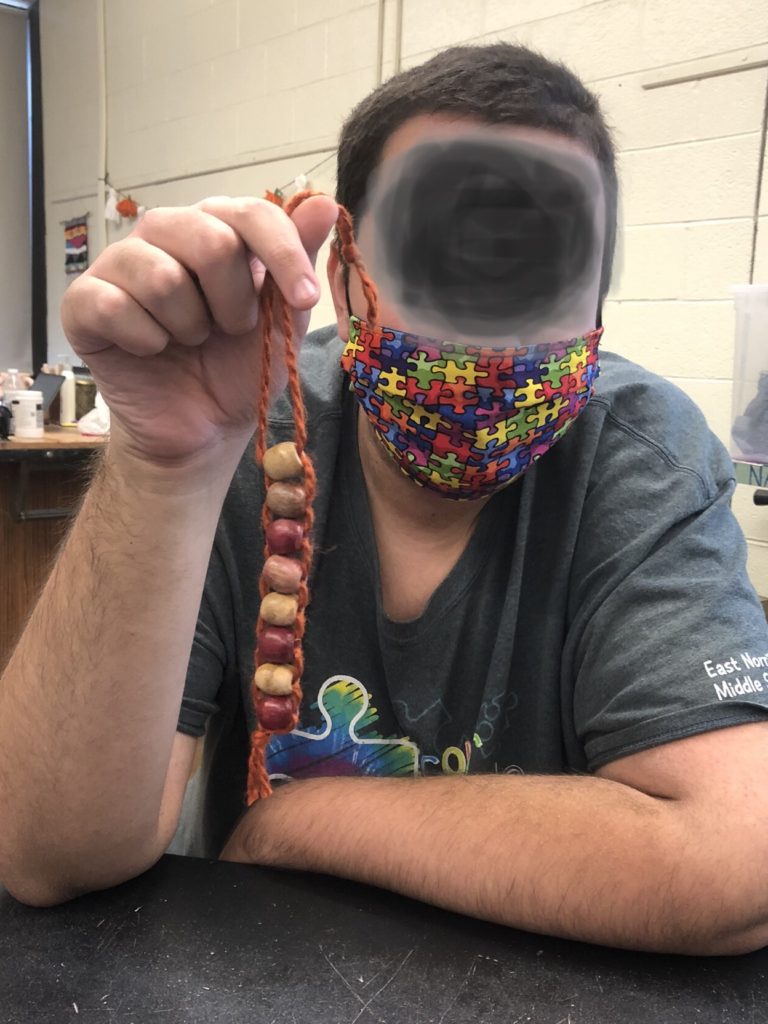

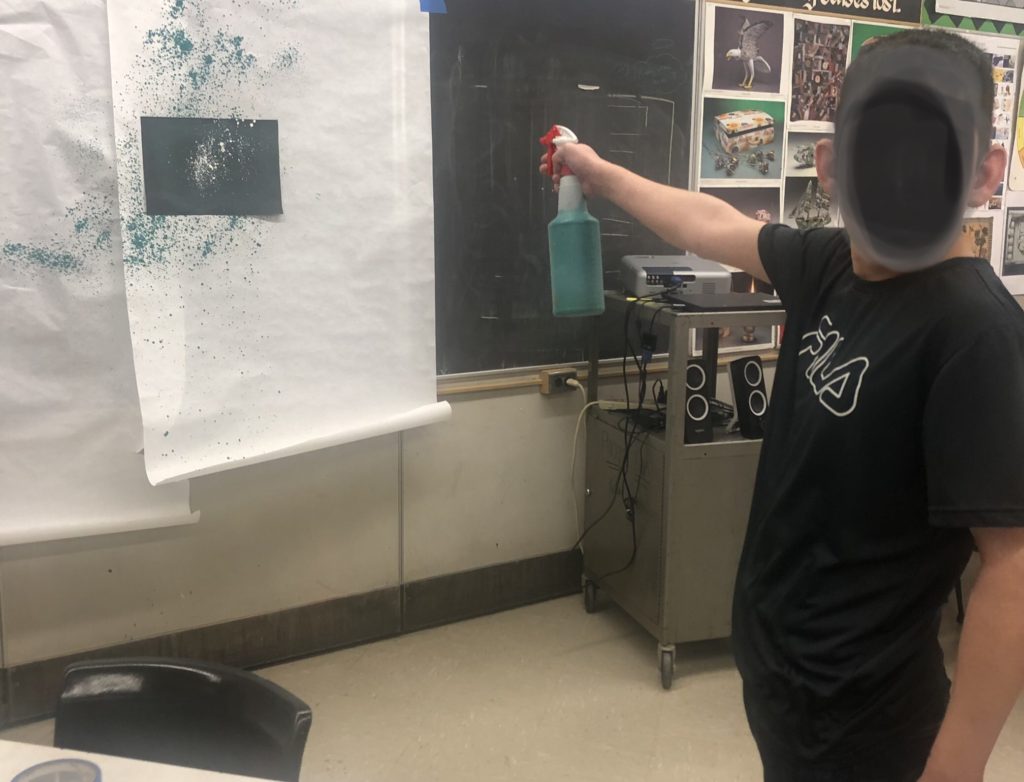

- Offer a variety of materials and methods

As a continuation of the last tip, always offer a variety of materials, tools, and methods. There are lots of great adapted materials available, and there are other resources to help you build your own adapted materials. Not all material or methods will work for every student so try it all and try it often. Sometimes it doesn’t “click” on the first try… that doesn’t mean it won’t “click” again later!

It’s hard to provide many different materials and opportunities without overstimulating some students or causing anxiety in others. When you introduce a new material, take it slow. Give lots of demonstrations. Show the different marks or methods to your students. Allow them to tactically engage in the material before they use it to create art. If the students become used to trying new things in a safe environment, they will likely be more receptive to taking the challenge you are giving them.

I’ll never forget a student several years ago that only made circular marks on paper. For weeks he engaged with markers, pencils, crayons, paint, and only created circular movements on his paper. One day he was given chalk pastels and he was captivated. Suddenly, his movements were controlled and intentional. He was deeply engaged in this material and he blew us all away. I would have never expected a chalk pastel to completely change one’s approach to art as drastically as it did. Opportunities for discovery exist everywhere so don’t leave any chances on the table!

- Take it slow and allow for deep exploration of concepts

Whether your curriculum is rigid or allows for lots of educator freedom, don’t try to cover too much material. This is harder than it seems!

Teachers have a lot of pressure on what they should cover and what their students should achieve. It’s extremely difficult to grapple with falling short of your own curricular expectations. However, your students will benefit greatly when you allow yourself to follow their lead, rather than the curricular documents that might not have been drafted with your specific students in this specific stage in mind. Accept that mastery might take longer and look different than you expected and embrace their pace. It is better to learn something thoroughly than be confused by many things!

- Pay attention to IEP goals

Empower yourself by becoming an active voice in the IEP process. In doing so, you will speak to your students from a lens that many others might not see. If you are not already invited to IEP meetings, ask to attend. This is a chance to hear all interested parties come together and you’ll end up seeing your student in a new light.

Pay attention to goals that may originally seem outside of your content. Functional or social goals are as crucial as any other academic-specific goals and all of them can manifest themselves in very meaningful ways in the art classroom. From counting out palettes to the proper pronunciation of new art terms, there are many ways that the art teacher can reinforce learning goals in very meaningful ways for the students.

I won’t claim that IEP documents aren’t daunting documents, but familiarizing yourself with each student’s IEP will help you reach your students in very significant ways.

- Fight for facilities adaptations

Are the students in wheelchairs able to move throughout the room? Are the tables/desks an appropriate height? Are your speakers loud enough for hearing impaired students to hear from anywhere in the room?

As you familiarize yourself with the IEP, it becomes more apparent where changes can be made to both your course and your classroom. While we can de-stimulate our classrooms and layout our furniture to better accommodate our students, some changes will require more support. Sometimes the changes can be small, such as using stools with narrow legs that don’t interfere with support canes but other times alternate seating such as balance balls or raised tables are needed. Don’t simply “accept the things you cannot change” and inform your administration of ways that student success can be impeded by facilities. In many cases, the administration might not be aware of the changes that you need, so do some research and state your cause!

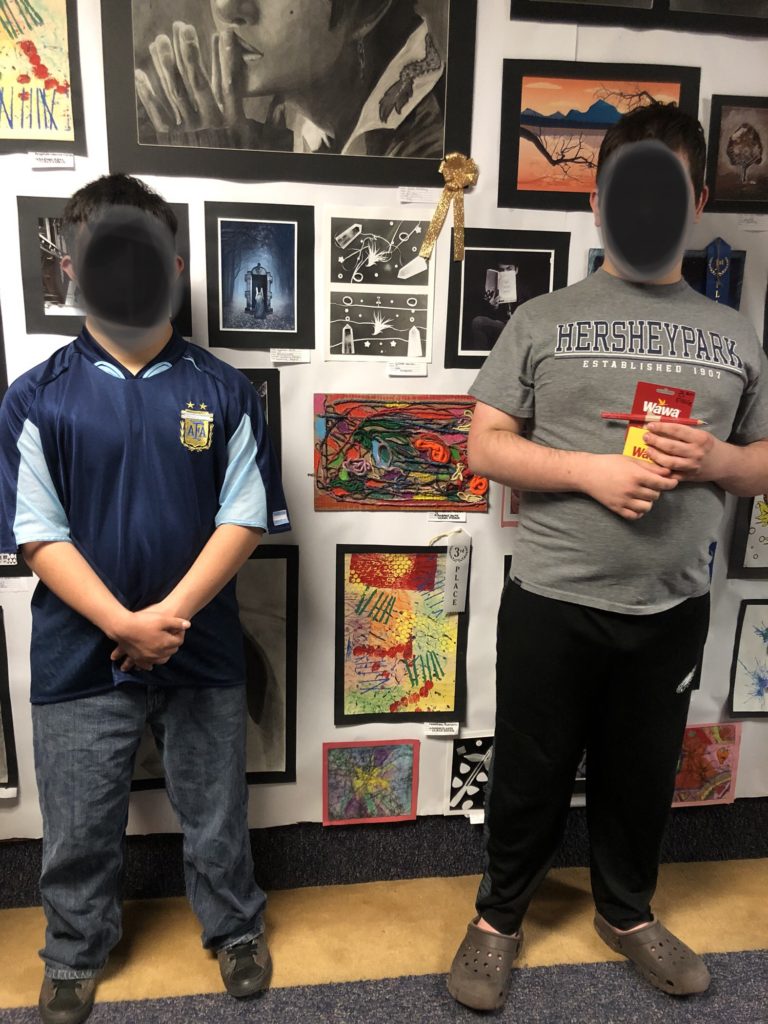

- Celebrate your students’ art within your community

This is another piece of advice that is more complicated in practice than it seems. In fact, I have talked with many other teachers of students with unique or multiple disabilities that have found the display and celebration of student work to be problematic.

Sometimes the finished product of your students’ work might not fit with the popular expectations of what age-appropriate school artwork might look like. I once had a display of Life Skills student work outside of my classroom and a visitor commented about the elementary art being displayed in a high school. That moment called for reflection for myself as well as our arts visitor.

I have struggled with how to frame my students’ work that doesn’t appear to mesh with the work of many public school art celebrations. Frankly, I find this to be a flaw in many juried shows. My students might not display the art skills that serve as exemplars for their grade levels, but they still show individuality, growth, and accomplishment and are worthy of display. At the same time, labeling the work as the product of a student with disabilities places the art in a category of Otherness.

The piece of advice to offer in this case is to start to carve out ways of changing the culture surrounding art by students with disabilities in your community. Consider how you label all student work to see if it categorizes students by age, ability, or disability. Educate your community about your program and continue to offer age-appropriate subject matter to your students with disabilities. Move to the freedom to proudly display your students’ work without disclaimers and labels so that all students feel more welcome to create and celebrate their creations in your classroom and beyond.

- Embrace authenticity

If we are going to celebrate the art that our students make, we must ensure that the work is exclusively theirs. If we are going to use their work as data in structuring IEP goals, we must make sure that the work we are evaluating is authentic.

There is a natural tendency to want to help our students. As a result, well-meaning adults often aid students in doing work that they can do themselves. The child might be capable of making marks on the page with the paintbrush, but they might not look like the representational landscape painting that others might be working on. As a result, sometimes adults will jump in and overly help or correct the students’ work. This is often done with the best intentions at heart.

It’s hard to stop yourself from “fixing” student artwork when it doesn’t turn out the way the project might have intended. It’s even harder to ask other adults (such as co-teachers or aids) to not interfere with the work. It’s incredibly hard when the other teacher or aid has a long and close relationship with that particular student.

Be firm in your role as an art educator. You are there to facilitate the childrens’ artwork and give them the space to grow. This growth might not look as perfect as the images that our biases create in our visions, but their artwork is unique to them, and, as teachers, strive to seek beauty in this authenticity.

- Consider your own curricular goals and philosophy of teaching

This job can be hard. It can be draining. It can be challenging and push you beyond what you thought you could (or should) have to do. But the small rewards that you achieve every day is likely the cause of why you chose this important and rewarding profession. Don’t let the mountains of paperwork and standardized assessments blur your vision of what you want to achieve with your students. If you ever feel stumped, frustrated, or depleted, remember what you wrote as your philosophy of art education before you accepted this job. How has this evolved as you’ve grown as an educator? Revise this statement often and reflect on the essentials of what you want to teach. Pause and remind yourself to be the teacher that you want to be. This job only feels challenging if you care deeply about the work you are doing, so embrace the journey and reward yourself for the growth you are making as an educator!

Further reading for consideration:

https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/health-wellness/2021/06/11/disabled-not-special-needs-experts-explain-why-never-use-term/7591024002/

D5 Creation

D5 Creation