How can we apply current debates and discussions about racial equity and social justice into our art curriculum?

Kristin Baxter, Ed.D. is an Associate Professor of Art and Director of the Art Education Program at Moravian College and member of Region 10 of PAEA. She also continues to teach children, adolescents, and families through her work as a mindfulness and art teacher at Shanti Project.

This spring the YWCA created an online “21-Day Racial Equity and Social Justice Challenge.”

https://www.ywcachallenge.org/session_catalog/#/attendee/B5364140-019C-4D80-82FB-FA101A6EA528/catalog Each day, since, April 19, I’ve received a selection of videos, articles, and podcasts curated around themes such as Reparations for Slavery; Reparations and Indigenous People; Ending the use of Native American Imagery in Sports; Intimate Partner Violence in the LGBTQ+ Community, among others. Like many of you, as I read, watch, listen to, and participate in debates and discussions, I am continually asking myself, how can I continue to build meaningful, robust content around racial equity and social justice in my art classes?

This blog entry describes how I’ve done this through Moravian College’s Town Hall program. I’ll also present ideas and questions that I will take to my classes in the future, that might spark some reflections for you too.

Moravian College hosts an annual Town Hall each spring. The Town Hall is made up of about 10 courses across disciplines, including over 150 students and faculty. When a faculty member agrees to teach a Town Hall course, they include a research project for their students based on one of four annual, academic themes: Healthcare; Sustainability; Poverty and Inequality; War, Peace, and the Just Society.

One of my art education methods courses, called Art Material Investigations: Processes and Structures, was one of the Town Hall courses this spring of 2021. My students researched contemporary artists whose work engages with one of those academic themes. During the virtual, online Town Hall event this past April, my students were placed in breakout rooms according to those academic themes. Each breakout room had roughly ten students from across all of the Town Hall classes, whose research fit within the same theme. Each group also included a faculty moderator and a community member, such as local school leaders, politicians, and business owners. In this way, the Town Hall fosters interdisciplinary discussion and action to solve critical issues for our contemporary world and demonstrates how interconnected many social, political, and economic problems are.

As a culminating part of their research, my students created their own works of art, based on the artists they researched. Through the use of a variety of processes and materials during our course, students also identify which art materials best communicate certain ideas.

One of my students, Janessa Ternosky, researched LaToya Ruby Fraizer, an African American activist and artist, who is well-known for her documentary-style black and white photographs that record the impact of environmental devastation on the health and well-being of marginalized families and communities in the Midwest. Inspired by Frazier’s work, Janessa created her own series of black and white photographs. Janessa explains, “my photo series, A Place Like Home, explores my childhood home and how the town I came from shaped and affected my family as a whole and ourselves individually” (Janessa Ternosky, personal communication, April 27, 2021).

Credit: Janessa Ternosky, Sister, 2021, and Grandpa, 2021 from the series, A Place Like Home. (Photos used with permission).

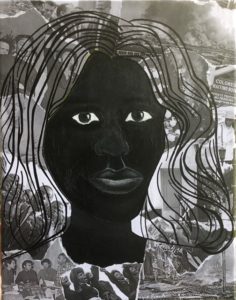

Another student, Ashlynn Forney, researched Kerry James Marshall, whose art references the Civil Rights Movement and addresses the “invisibility of Black people in America and the unnecessarily negative connotations associated with darkness” (Art21, 2021, para. 4). Ashlynn’s mixed media piece, entitled “Impactful Faces” was inspired by Marshall’s mixed media work “Untitled Self-Portrait (Supermodel) from 1994. Ashlynn explains that “a variety of historical photos that display instances of racial injustice, segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and impactful individuals during those moments were strategically places around the painted portrait” (Ashlynn Forney, personal communication, May 2, 2021).

Credit: Ashlynn Forney, Impactful Faces, 2021, mixed media on canvas, 11” x 14.” Inspired by Kerry James Marshall’s work “Untitled Self-Portrait (Supermodel), 1994, mixed media on paper, 1994. (Photo used with permission).

Through participating in the Town Hall and also in the YWCA’s “21-Day Racial Equity and Social Justice Challenge,” I wrestle with questions that I could use to prompt discussion and artmaking in my classes next semester.

Perhaps these reflections might also inspire you to see how issues of racial equity and social justice could impact your teaching too:

- Danielle Bainbridge (2020, December 9), in her video titled The History of Reparations, describes how the City of Chicago paid reparations to victims of Jon Burge, police commander. From the 1970s-1990s, Burge led police officers to torture Black men into giving confessions for crimes they did not commit. Part of the reparations that were part of the settlement included mandatory curriculum in the Chicago public school system about Burge’s crimes. What role do you think public school, PreK-12 education in general, and art education curriculum design in particular, could play in reparations?

- Has your favorite sports team changed its name, mascot, and/or logo because it was originally racist? How were multiple cultural perspectives and organizations involved in choosing the new name? Imagine that you need to create a new name, logo, and mascot for your team, what steps would you take to create these? Who would be involved in the designs? Dr. Anton Treuer (2019, December 13), Professor of Ojibwe and Native American author, argues that we need to have ethics around this issue in sports culture. What role does the study of ethics play in design and art education?

- Amy Graff (2017, August 30), in her article titled, “The next generation of California public school students will skip the ‘mission project’,” she describes how the “fourth-grade tradition of building a California mission out of Popsicle sticks and sugar cubes is being pushed aside by the state as history lessons change to reflect all cultures and more accurately depict the past” (para. 1). In addition to ignoring how the missionaries impacted the Native people in the area, the art project had few meaningful art learning objectives. One parent is quoted in the article as remarking: “I was so relived they didn’t have to build that dumb building (as I did back in 1980) and that they got a fuller picture of life in California at that time” (para. 10). How are art projects that are meant to broaden understanding about cultures actually racist and support stereotypes? If your current art education curriculum includes a culture- or history- based project, how might you reflect on its relevance? Is that project culturally biased or even racist?

- 80% of women and children who have experienced homelessness have also experienced domestic violence (National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017, May 30). Survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault urgently need safe and affordable housing. Have students research the types housing options that should be available in our communities, like emergency shelters, transitional housing, and permanent supportive housing, among others. How could we design an art lesson based on a discussion of housing options within a neighborhood and community? How does the design of a community reflect and support the diverse needs of the people who live there?

References

- Art21. (2021). Kerry James Marshall. Art21. https://art21.org/artist/kerry-james-marshall/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwp86EBhD7ARIsAFkgakh7lCLVi1VYWGsYFiY2XS2KzdTz1d0_QBdzh1zucruwU2rwwyfbHacaAi-REALw_wcB

- Bainbridge, D. (2020, December 9). The History of Reparations. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98u7NNBWsMU&ab_channel=OriginOfEverything

- Graff, A. (2017, August 30), The next generation of California public school students will skip the ‘mission project.’ SFGATE.com. https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/California-public-schools-mission-project-model-11953722.php

- National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. (2017, May 30). The Intersection of Homelessness and Domestic Violence. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVnwGFqyEcQ&ab_channel=NationalResourceCenteronDomesticViolence

- Treuer, A. (2019, December 13). Not Your Mascot: Native Americans and Team Mascots. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orVEuhZsRgo&ab_channel=TPTOriginals

D5 Creation

D5 Creation