PART II: Game Inspired Creative Processes

Gaming your Pedagogy:

Taking inspiration from games, toys and play in the art classroom

Renee Jackson is an Assistant Professor and Program Head of Art Education at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, in the Art Education and Community Arts Practices Department at Temple University. She is an artist, critical feminist pedagogue, and scholar, whose research interests relate to the disruption of oppressive mechanisms in education and the integration of game-design and game-play as collaborative art forms and learning tools, in support of this goal. Jackson has worked as an art educator for 21 years at all levels and in various contexts.

Part 2: Game Inspired Creative Processes

Games of Chance

Many games rely on combinations of chance and strategy. The Dadaists and Surrealists valued chance as a means of undermining logic and reason, and of escaping the deep, dead tracks of linearity. One of the primary ways that they accomplished this was through games and play. For the Surrealists, “games and procedures are intended to free words and images from the constraints of the rational and discursive order, substituting chance and indeterminacy for premeditation and deliberation.” (Brotchie & Gooding, 1995, p. 10). From the Dadaist perspective, Phillip Prager (2013) argues that negative interpretations of Dadaism through the lens of nihilism and the trauma of war fails to value them as the visionaries they were, centering play “as a fundamental expression of humanity, long before academia would take adult play seriously.” (p. 239)

This blog entry is about reclaiming the magic of chance as a creative process as celebrated by these two movements, with a nod to the idea of artistic inquiry through constraints that enable (Castro, 2007).

The Surrealists spent much of their time playing a wide assortment of such games (Brotchie & Gooding, 1995). Among these games, several are common in art education circles. The process of creating found poetry, originally conceived by Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara is quite well known for example. Tzara describes the process of making a Dadaist poem: cut up a newspaper article; drop the words in a bag; shakes it up; draw them out one by one; place them in the order they appear, thus creating a poem: “that will be like you” (p. 36). Similarly, from a visual perspective, Hans Arp dropped shapes onto paper to create collages. The game known as the Exquisite Corpse, where one begins a drawing, folds the paper to hide it from the next person, and then passes it along, of course, is also a classic. Other Surrealist games are lesser-known. For example, there are many such collective “chain games” that involve concealment, often of text, in order to reveal/elicit surprising, often rather humorous or profound results. In “Definitions/ Questions and Answers” one player writes a question, folds the piece of paper, and passes it to another player who writes an answer. “What is reason? A cloud eaten by the moon.” (Broachie, 1995, p. 26).

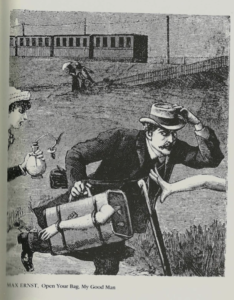

Visually, Decalomania is the process of spreading a liquidy medium onto a non-absorbent surface and laying an absorbent piece of paper on top, and then removing it. Coulage is a process where one pours a molten material such as wax or chocolate into water to form a spontaneous sculpture. Collage of course played an important role in both Dadaism and Surrealism using both image and text. Max Ernst would gather images with a similar look/style ie/ etching and mix them together to form seamless collages producing bizarre/fantastical images.

A fun version of this is to fill a spray bottle with ink and invite students to take aim at a paper/canvas/wall target. This work can then be either titled right away or built upon by highlighting details and adding other media.

Thread-tiles is a project I originally created with students in grades 4 & 5. Based on my own series of drawings with hair on tiles inspired by shower doodles (if you have long hair, you know what I’m talking about!), students drop embroidery thread, or combinations of types of thread/string on a wet tile (gently mist with a spray bottle) and play with them until they see an interesting image. The image can then be adhered by using a small brush dipped in glue and dabbed along the lines of the thread. It is fun to name these “thread-tiles” based on every detail taking place in the image. For example in the image below: A devil wearing a zig-zag shirt, stepping on magical grass with a cloud that points out that it will rain by Nora, grade 4.

Building from this idea of chance as a disruptive mechanism, I find decks of cards a handy vessel through which to bring these notions to life.

Decks of Cards

Various types of decks of cards can offer this combination of chance and play within the creative process. Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt created Oblique Strategies in 1975, a deck of cards meant to offer inspiration, particularly when one is creatively blocked. Students of course can invent their own versions inspired by Eno and Schmidt. Examples: “What would your closest friend do?” or “Destroy nothing: Destroy the most important thing.” You can play with an online version here

Imagination Cards: Decks 1 – 3

I developed a series of decks of imagination cards (Imagination 1 – 3), that students can both draw from and contribute to. We often used them to exercise the imagination in our sketchbooks, but they could also be used as a starting point for more elaborate works. The first deck consists of a series of prompts that engage and exercise the imagination in a direct way. Some examples from me: If you had a grandma with a cane and wings, what would she look like if she flew past the window? (Illustration by Annabel, grade 8?) If you planted a human organ (heart, lungs, stomach….) what would grow? If the sun went out, how could you replace it? Student examples: If all of the planets were animals, what would they look like? What would your time machine look like?

The decks become increasingly complex. Deck 2 consists of random objects combined with the cards. Reach into a bag for the object and then draw a card: How could this be used as a utensil? Whose is this? Who lives here? If it was part of a hat, what would the hat look like?

Deck 3 involves using the objects and combining them with the surrounding environment to create a scene. The teacher and students can take turns setting up a scene and then asking questions about it that can be responded to visually and/or in writing. Imagine a scene for example where desks are tipped over, and creatures are crawling out of 7 cracked eggshells. Questions are then drawn from the deck: What happened? Who inspired this? Where did they come from?

Quest Ions

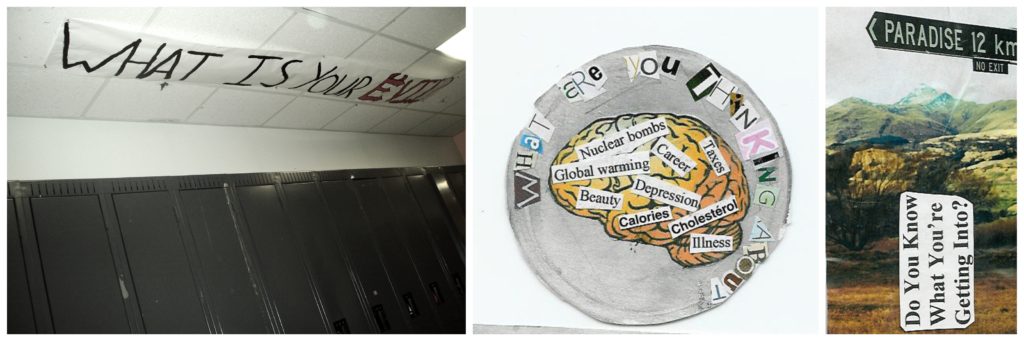

Quest Ions is a deck of cards meant to help the player to interrogate taken-for-granted assumptions. They encourage one to consider details about the world on a deeper level. Again, both teacher and students come up with questions to add to the Quest Ion deck. Here are some of my original examples: What are your tasks? Who defines “normal”? Why are wrinkles considered “bad”? Why do children tend to have better imaginations than adults?

From grade 8 students:

- Are we getting dumber or smarter?

- Why do people try to be similar?

- Where do you draw the line?

- What defines good taste?

- Is there such a thing as paradise?

- Is it more important to have questions or answers?

These cards can be used in a variety of ways. Students came up with such questions as an introductory exercise to a larger project where they juxtaposed unexpected images with their questions in order to provoke new ways of thinking (Barbara Kruger style) in the form of buttons, magnets, and postcards. Students painted their questions as large-scale banners that were hung around the school to inspire the school community to contemplate life on a deeper level. Performance art can ensue when students sit down together, draw a card and take turns discussing the question. This can be timed, taking turns responding every minute or two, or to be more absurd, responding simultaneously to the same question. Many types of rules can be invented for Quest Ion performance games!

Fascinating Facts

This deck of cards was the basis for a collective series of works by the entire student population created for our annual art exhibition, this particular year titled: Finding Fascination. Students gathered fascinating facts, and we built a deck of cards. The challenge was to create an artwork that reflects a fact from the deck, with the fact embedded within the artwork for the viewer to find. The installation of fascinating facts artworks then became a game in itself where the viewer could pluck the work from the wall and try to guess and find the fact. At the end of the exhibition, students drew numbers and took home the work of another student.

Some examples of Fascinating Fact cards:

In the Elizabethan age, lovers exchanged “love apples”. A woman would keep a peeled apple in her armpit until it was saturated with her sweat, and then give it to her sweetheart to inhale. (Ackerman, 1991, p. 24).

When threatened, a sea cucumber barfs up its own guts for the enemy to eat and then grows new ones. (National Geographic).

A duck’s quack doesn’t echo, and no one knows why (Illustration by Emma, grade 7).

The average human will grow 590 miles of hair (Illustration by Laura, grade 12)

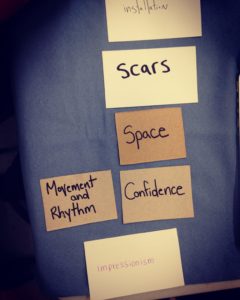

Molecular Equation Cards or Chance-Based Art Education.

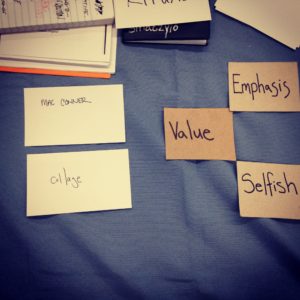

And finally, this approach is about playing with the idea of choice-based art education by adding the chance element as a twist. Elements and principles cards, moods/emotion cards, concept cards, are what I think of as “molecules”, that can be combined together and channeled through a particular student or group of students to form a work of art. Other types of cards could also be added of course (nouns and verbs for example).

Students can also roll dice, draw cards, or be blindfolded and spun around while pointing to select a medium to add to the equation. This technique can also be used by art educators to come up with new project ideas.

Conclusion

The Dadaists and Surrealists revered the magic of chance encounters and exploited it magnificently in their lives and creative actions. Combining chance with strategy/purposefulness in our creative processes can subvert habits, lead to new approaches and exciting discoveries, and help us to interrogate assumptions and taken-for-granted traditions.

References

- Ackerman, D. (1991). A natural history of the senses. Vintage Books.

- Brotchie, A., & Goooding, M. (Eds.). (1995). The book of surrealist games. https://monoskop.org/images/e/e0/Brotchie_Alastair_Gooding_Mel_eds_A_Book_of_Surrealist_Games_1995.pdf

- Castro, J.C. (2007). Constraints that enable : Creating spaces for artistic inquiry. Proceedings of the 2007 complexity science and educational research conference https://silo.tips/download/constraints-that-enable-creating-spaces-for-artistic-inquiry

- Eno, B. & Schmidt, P. (1975). Oblique Strategies. https://obliquestrategies.ca/#

- National Geographic. Sea cucumber. Natinal Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/sea-cucumbers

D5 Creation

D5 Creation