The Power of Storytelling

Carla Rodrigues is the K-5 Remote Art Teacher for the Easton Area School District where she currently teaches students from all seven elementary schools. Carla shares a personal memoir with a guiding interest in storytelling in the classroom.

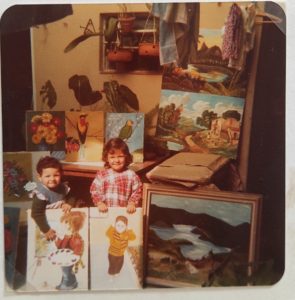

In my teenage years, I was convinced that telling stories from the past would hold me back. After all, those were the years I could not wait to leap into the future. Ironically, as I get older and my children grow up and take flight, I find myself telling them stories in an attempt to keep memories alive. Recently, my mother sent me a photograph that captures a family story that I told my children, bringing together some of the bits and pieces they had heard from me before.

It was 1979. I was visiting Brazil with my younger sister Anita and my mother. The paintings around us (see image above) were made by my maternal grandmother. I still remember how the oil paint and turpentine felt almost inebriating. Struggling to sustain a growing family in Portugal on two low-income teaching salaries, my parents started to look for other places where we could live more comfortably. Brazil was one of those places. Nonetheless, we never ended up moving there.

It was 1979. I was visiting Brazil with my younger sister Anita and my mother. The paintings around us (see image above) were made by my maternal grandmother. I still remember how the oil paint and turpentine felt almost inebriating. Struggling to sustain a growing family in Portugal on two low-income teaching salaries, my parents started to look for other places where we could live more comfortably. Brazil was one of those places. Nonetheless, we never ended up moving there.

My grandmother aspired to be a professional artist. Instead of pursuing her passion full-time, she raised her children and grandchildren, attended classes, and painted whenever she could. She had only lived in Brazil for three years. The Angolan Civil War of 1975 forced her to leave behind their farmland and family house that my grandfather built for their family of seven. My grandmother’s paintings were of real and imaginary things, merging old with new dreams, but rarely depicted resentment and sorrow despite her circumstances.

It was during the family’s escape from the war that my mother left her family and went to Portugal. She was newly married to my father and carried me in her womb when they flew to his native land in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the island of São Miguel. I was born and raised rooted in the land, but with my eyes on the horizon of the sea. The desire to explore and add something beautiful and useful to the world remains the same after all these years. I believe this is part of the reason why I currently live in the United States of America and teach Visual Arts to children.

My grandmother is no longer with us. 2020 took her at 96 years old. The stories she told us through her paintings will keep her alive in our memories. I understand now that storytelling takes us back to the past, but it can also propel us into the future, which is now more uncertain than ever. I’m sure that we will be telling COVID-19 related stories for years to come and they won’t be all sad. I heard many stories of hope in the middle of loss and despair during war times and arduous beginnings. Storytelling can help us paint our lives with gratitude and hope. It’s a form of art and an art of many forms.

I see great benefits of incorporating storytelling in Visual Arts instruction, especially in Art History lessons. This year, for example, when learning about Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), before introducing any information about the artist and his art, I provided second-grade students with an image of one of his paintings (Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005). The students were asked to observe the painting very carefully and use its details to develop a short story with a beginning, middle, and end, imagining what could have happened before, during, and after that very moment captured by the artist. Given the digital platform that my students use for virtual learning, they recorded their own voices telling the stories and sharing them with me. I then displayed a painting by Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). When looking at this painting (Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1800-1) and Wiley’s painting, side by side, the students compared and contrasted both paintings and drew conclusions about the relationship between the two. What started with a storytelling exercise evolved into insightful and powerful discussions about subject matter and form, historical and cultural contexts of artwork from different times and places in the world, touching upon a variety of art, literature, history, social science standards while making connections to current events.

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005 (Left) – Jacques-Louis David, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1800-01 (Right).

In another example (pre-COVID), when introducing first-grade students to Abstract Art and its pioneer Wassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944), I played a classical theme from Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840-1893). First, I had the students listen to the music with their eyes closed and imagine it as a sequence of events or a story. Students shared out single words such as peaceful, happy, sad, and scary to describe particular parts of their stories. Together, we matched each word with a color (peaceful/light blue, sad/grey, happy/yellow, scary/dark red). The students then shared their stories with one another as they helped each other with selecting pieces of colored paper that best described their respective stories. As the students listened to the music one more time, they cut out geometric and organic shapes, pasted them on larger pieces of white paper, and added different kinds of black lines over and around the shapes. After a gallery walk, as we listened to the music one last time and commented on each other’s work, I asked, “What if we could actually see sounds?” This set the stage to finally introduce Kandinsky and his artwork, synesthesia, and abstract art. This lesson not only allowed the application of the students’ prior knowledge of shape and line quality, but also enabled them to develop their compositional, art interpretation, collaboration, and communication skills, and make connections between their artwork and the work of Kandinsky in a more authentic way. Since I taught this lesson, a few complementary digital tools have been developed and made available through Google Arts & Culture (https://artsandculture.

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925

Storytelling skills can also be applied to older grades. In fourth and fifth grade, for example, when reflecting on their artwork and writing artist statements, students start by describing their individual creative processes from beginning to end in order to identify the how and why of their work. I often use Georgia O’Keefe as a reference when she wrote, “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else… Nobody really sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time… So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.” In this brief story, O’Keeffe describes her how and why in very simple terms. Have you noticed how naturally students default to storytelling when making connections between their work and a special event in their lives, person, or memory anyway?

I now understand that storytelling helps us make sense of who we are. It establishes our roots so we can rise up even stronger. It uniquely draws our experiences in the sketchbook of life so, as we flip through its pages, we can see a path behind us and feel a sense of direction and purpose ahead of us. Storytelling is personal, so is the art we make. And, every time we tell a story or share our art, we commune with the world.

If you use storytelling in your classroom, I would love to hear from you! You can message me via email at region10@paea.org, Instagram @rodrigues.art.classes, Facebook @mrsrodriguesartclasses, or Twitter @EASDRodrigues.

*Cassidy Kandinsky lesson via collaboration with student-teacher Anna Nestor

D5 Creation

D5 Creation