Uncategorized

now browsing by category

PART II: Game Inspired Creative Processes

Gaming your Pedagogy:

Taking inspiration from games, toys and play in the art classroom

Renee Jackson is an Assistant Professor and Program Head of Art Education at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, in the Art Education and Community Arts Practices Department at Temple University. She is an artist, critical feminist pedagogue, and scholar, whose research interests relate to the disruption of oppressive mechanisms in education and the integration of game-design and game-play as collaborative art forms and learning tools, in support of this goal. Jackson has worked as an art educator for 21 years at all levels and in various contexts.

Part 2: Game Inspired Creative Processes

Games of Chance

Many games rely on combinations of chance and strategy. The Dadaists and Surrealists valued chance as a means of undermining logic and reason, and of escaping the deep, dead tracks of linearity. One of the primary ways that they accomplished this was through games and play. For the Surrealists, “games and procedures are intended to free words and images from the constraints of the rational and discursive order, substituting chance and indeterminacy for premeditation and deliberation.” (Brotchie & Gooding, 1995, p. 10). From the Dadaist perspective, Phillip Prager (2013) argues that negative interpretations of Dadaism through the lens of nihilism and the trauma of war fails to value them as the visionaries they were, centering play “as a fundamental expression of humanity, long before academia would take adult play seriously.” (p. 239)

This blog entry is about reclaiming the magic of chance as a creative process as celebrated by these two movements, with a nod to the idea of artistic inquiry through constraints that enable (Castro, 2007).

The Surrealists spent much of their time playing a wide assortment of such games (Brotchie & Gooding, 1995). Among these games, several are common in art education circles. The process of creating found poetry, originally conceived by Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara is quite well known for example. Tzara describes the process of making a Dadaist poem: cut up a newspaper article; drop the words in a bag; shakes it up; draw them out one by one; place them in the order they appear, thus creating a poem: “that will be like you” (p. 36). Similarly, from a visual perspective, Hans Arp dropped shapes onto paper to create collages. The game known as the Exquisite Corpse, where one begins a drawing, folds the paper to hide it from the next person, and then passes it along, of course, is also a classic. Other Surrealist games are lesser-known. For example, there are many such collective “chain games” that involve concealment, often of text, in order to reveal/elicit surprising, often rather humorous or profound results. In “Definitions/ Questions and Answers” one player writes a question, folds the piece of paper, and passes it to another player who writes an answer. “What is reason? A cloud eaten by the moon.” (Broachie, 1995, p. 26).

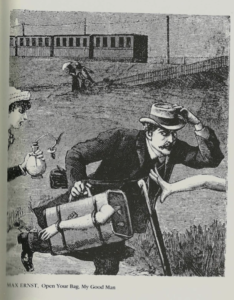

Visually, Decalomania is the process of spreading a liquidy medium onto a non-absorbent surface and laying an absorbent piece of paper on top, and then removing it. Coulage is a process where one pours a molten material such as wax or chocolate into water to form a spontaneous sculpture. Collage of course played an important role in both Dadaism and Surrealism using both image and text. Max Ernst would gather images with a similar look/style ie/ etching and mix them together to form seamless collages producing bizarre/fantastical images.

A fun version of this is to fill a spray bottle with ink and invite students to take aim at a paper/canvas/wall target. This work can then be either titled right away or built upon by highlighting details and adding other media.

Thread-tiles is a project I originally created with students in grades 4 & 5. Based on my own series of drawings with hair on tiles inspired by shower doodles (if you have long hair, you know what I’m talking about!), students drop embroidery thread, or combinations of types of thread/string on a wet tile (gently mist with a spray bottle) and play with them until they see an interesting image. The image can then be adhered by using a small brush dipped in glue and dabbed along the lines of the thread. It is fun to name these “thread-tiles” based on every detail taking place in the image. For example in the image below: A devil wearing a zig-zag shirt, stepping on magical grass with a cloud that points out that it will rain by Nora, grade 4.

Building from this idea of chance as a disruptive mechanism, I find decks of cards a handy vessel through which to bring these notions to life.

Decks of Cards

Various types of decks of cards can offer this combination of chance and play within the creative process. Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt created Oblique Strategies in 1975, a deck of cards meant to offer inspiration, particularly when one is creatively blocked. Students of course can invent their own versions inspired by Eno and Schmidt. Examples: “What would your closest friend do?” or “Destroy nothing: Destroy the most important thing.” You can play with an online version here

Imagination Cards: Decks 1 – 3

I developed a series of decks of imagination cards (Imagination 1 – 3), that students can both draw from and contribute to. We often used them to exercise the imagination in our sketchbooks, but they could also be used as a starting point for more elaborate works. The first deck consists of a series of prompts that engage and exercise the imagination in a direct way. Some examples from me: If you had a grandma with a cane and wings, what would she look like if she flew past the window? (Illustration by Annabel, grade 8?) If you planted a human organ (heart, lungs, stomach….) what would grow? If the sun went out, how could you replace it? Student examples: If all of the planets were animals, what would they look like? What would your time machine look like?

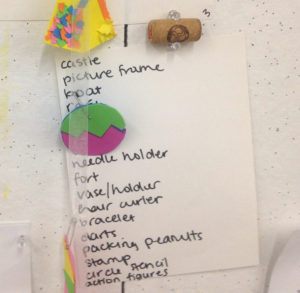

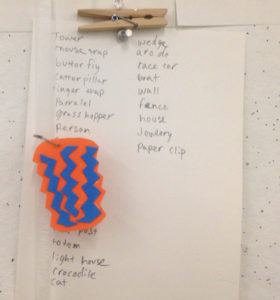

The decks become increasingly complex. Deck 2 consists of random objects combined with the cards. Reach into a bag for the object and then draw a card: How could this be used as a utensil? Whose is this? Who lives here? If it was part of a hat, what would the hat look like?

Deck 3 involves using the objects and combining them with the surrounding environment to create a scene. The teacher and students can take turns setting up a scene and then asking questions about it that can be responded to visually and/or in writing. Imagine a scene for example where desks are tipped over, and creatures are crawling out of 7 cracked eggshells. Questions are then drawn from the deck: What happened? Who inspired this? Where did they come from?

Quest Ions

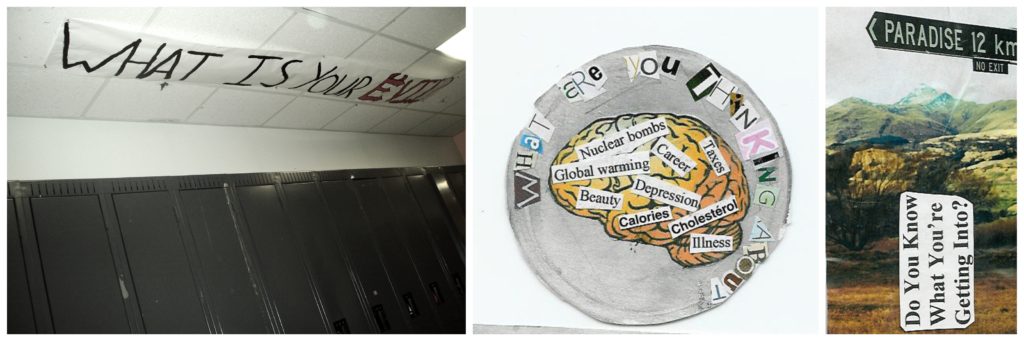

Quest Ions is a deck of cards meant to help the player to interrogate taken-for-granted assumptions. They encourage one to consider details about the world on a deeper level. Again, both teacher and students come up with questions to add to the Quest Ion deck. Here are some of my original examples: What are your tasks? Who defines “normal”? Why are wrinkles considered “bad”? Why do children tend to have better imaginations than adults?

From grade 8 students:

- Are we getting dumber or smarter?

- Why do people try to be similar?

- Where do you draw the line?

- What defines good taste?

- Is there such a thing as paradise?

- Is it more important to have questions or answers?

These cards can be used in a variety of ways. Students came up with such questions as an introductory exercise to a larger project where they juxtaposed unexpected images with their questions in order to provoke new ways of thinking (Barbara Kruger style) in the form of buttons, magnets, and postcards. Students painted their questions as large-scale banners that were hung around the school to inspire the school community to contemplate life on a deeper level. Performance art can ensue when students sit down together, draw a card and take turns discussing the question. This can be timed, taking turns responding every minute or two, or to be more absurd, responding simultaneously to the same question. Many types of rules can be invented for Quest Ion performance games!

Fascinating Facts

This deck of cards was the basis for a collective series of works by the entire student population created for our annual art exhibition, this particular year titled: Finding Fascination. Students gathered fascinating facts, and we built a deck of cards. The challenge was to create an artwork that reflects a fact from the deck, with the fact embedded within the artwork for the viewer to find. The installation of fascinating facts artworks then became a game in itself where the viewer could pluck the work from the wall and try to guess and find the fact. At the end of the exhibition, students drew numbers and took home the work of another student.

Some examples of Fascinating Fact cards:

In the Elizabethan age, lovers exchanged “love apples”. A woman would keep a peeled apple in her armpit until it was saturated with her sweat, and then give it to her sweetheart to inhale. (Ackerman, 1991, p. 24).

When threatened, a sea cucumber barfs up its own guts for the enemy to eat and then grows new ones. (National Geographic).

A duck’s quack doesn’t echo, and no one knows why (Illustration by Emma, grade 7).

The average human will grow 590 miles of hair (Illustration by Laura, grade 12)

Molecular Equation Cards or Chance-Based Art Education.

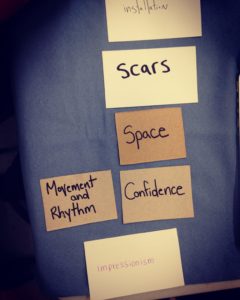

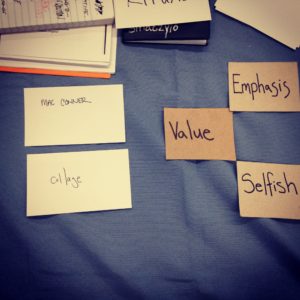

And finally, this approach is about playing with the idea of choice-based art education by adding the chance element as a twist. Elements and principles cards, moods/emotion cards, concept cards, are what I think of as “molecules”, that can be combined together and channeled through a particular student or group of students to form a work of art. Other types of cards could also be added of course (nouns and verbs for example).

Students can also roll dice, draw cards, or be blindfolded and spun around while pointing to select a medium to add to the equation. This technique can also be used by art educators to come up with new project ideas.

Conclusion

The Dadaists and Surrealists revered the magic of chance encounters and exploited it magnificently in their lives and creative actions. Combining chance with strategy/purposefulness in our creative processes can subvert habits, lead to new approaches and exciting discoveries, and help us to interrogate assumptions and taken-for-granted traditions.

References

- Ackerman, D. (1991). A natural history of the senses. Vintage Books.

- Brotchie, A., & Goooding, M. (Eds.). (1995). The book of surrealist games. https://monoskop.org/images/e/e0/Brotchie_Alastair_Gooding_Mel_eds_A_Book_of_Surrealist_Games_1995.pdf

- Castro, J.C. (2007). Constraints that enable : Creating spaces for artistic inquiry. Proceedings of the 2007 complexity science and educational research conference https://silo.tips/download/constraints-that-enable-creating-spaces-for-artistic-inquiry

- Eno, B. & Schmidt, P. (1975). Oblique Strategies. https://obliquestrategies.ca/#

- National Geographic. Sea cucumber. Natinal Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/sea-cucumbers

Solidarity and the Art of Sonya Clark

Sue Uhlig is the PAEA Region 4 Representative and is a Ph.D. candidate in Art Education at Penn State University. She also teaches online classes for Purdue and Illinois State. Sue’s interests include object collections as research and artistic practice, traveling, and hiking with her husband and pup.

I was first introduced to the work of artist Sonya Clark in 2007 when she came to Purdue University for a hands-on workshop on beaded prayer packets, which corresponded to the exhibition Beaded Blessings she curated. In the Beaded Prayer Project, Clark asked people all over the world to make beaded prayer packets individually or through workshops and displayed them in Beaded Blessings. The workshop led participants through the process of creating a prayer packet using scraps of fabric, beads, and thread to enclose a handwritten wish, prayer, hope, or dream. It was powerful to see the hundreds of contributions of beaded prayer packets from people all over the world in the accompanying exhibition. After the workshop, participants were able to add their contributions to the show, which allowed me to see the possibilities of a participatory gallery show in which all contributions were valued.

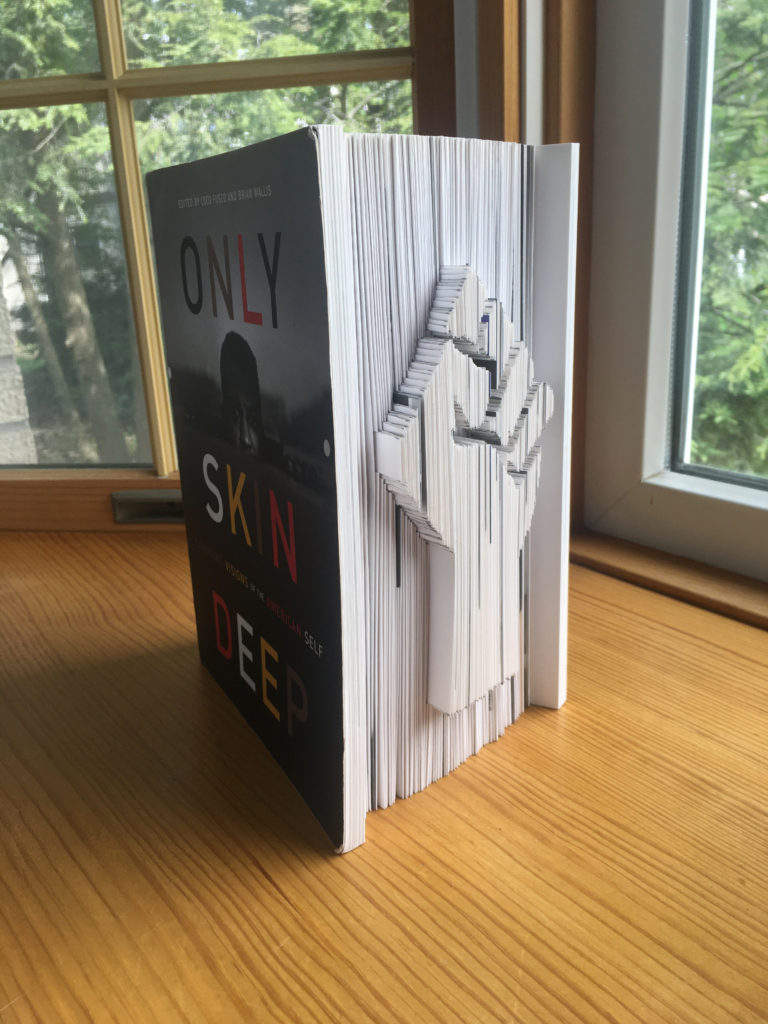

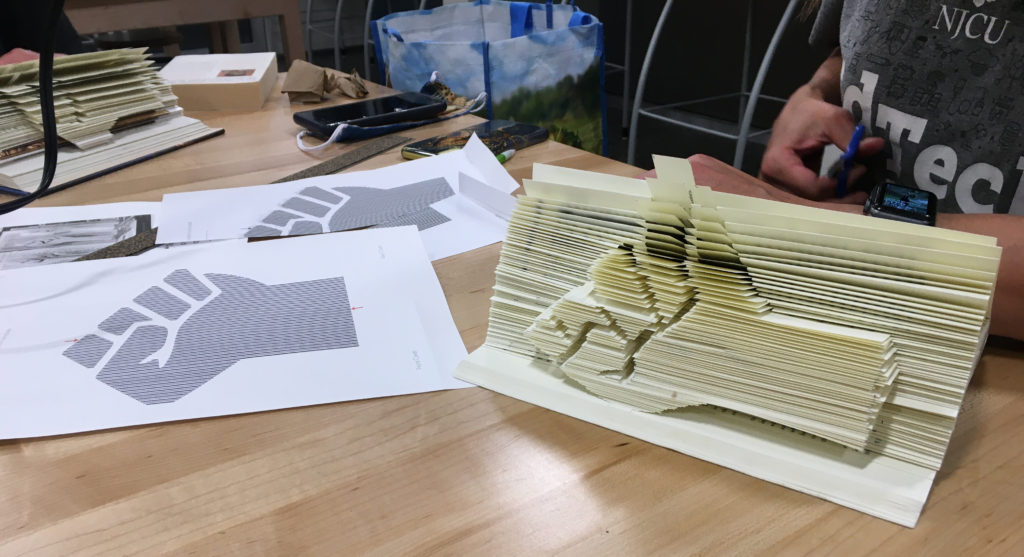

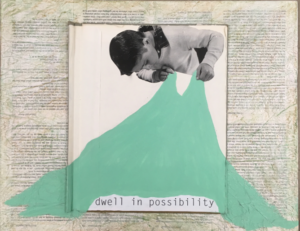

Flash forward to 2021- I saw images for the Solidarity Book Project on social media, and I was excited to see that initiative was led by Sonya Clark. The Solidarity Book Project asks us to reflect on the concept of solidarity through art, particularly with Black and indigenous communities. Once again, the exhibition is participatory in nature and consists of open contributions by a variety of participants.

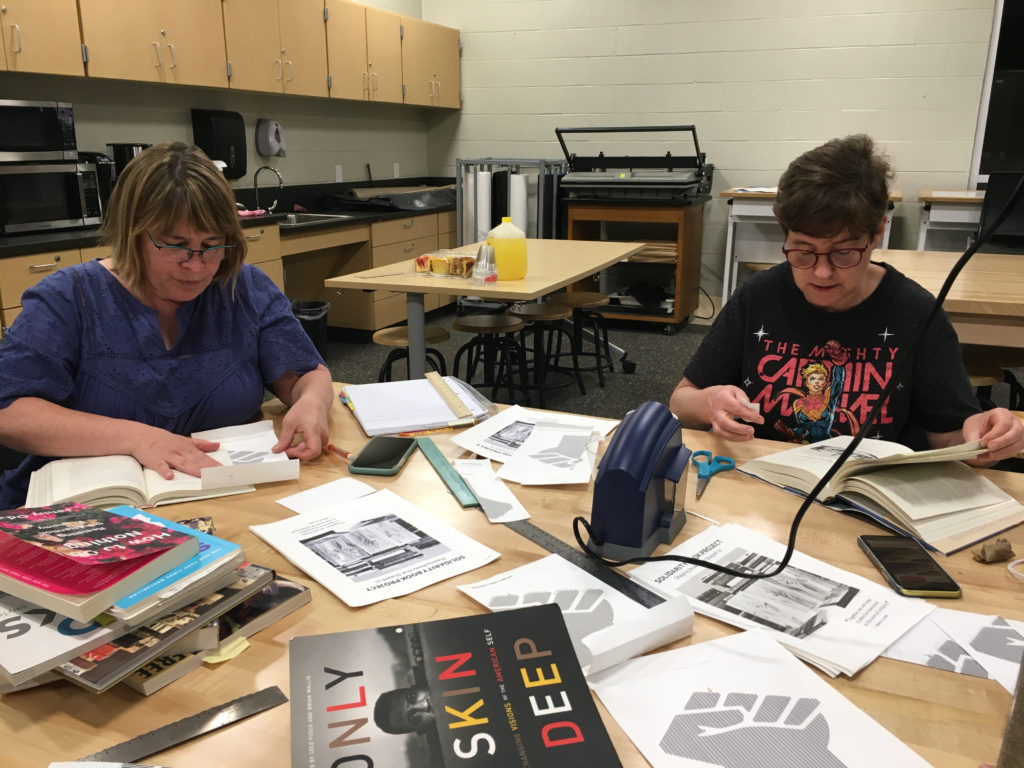

Last month, I led a Region 4 workshop on the Solidarity Book Project during which participants Amy Anderson, Julia Nelson, and Danielle Crowe sculpted a book that taught them something about solidarity. I also asked participants to submit a statement on what solidarity means to them, and I included their statements in social media posts. Their books will be included in the upcoming exhibition at Amherst College.

Submissions for the Solidarity Book Project are accepted until June 30, so it’s not too late to make your own book and submit it for the exhibition! Follow the directions on the website to sculpt your book and mail it to Amherst College. In lieu of or in addition to the book, you can submit your statement on solidarity and/or a recording of you reading a short passage from a book that has taught you something about what solidarity means. Each participatory act raises money for Black and indigenous communities. See the Solidary Book Project website for more details in how you can participate.

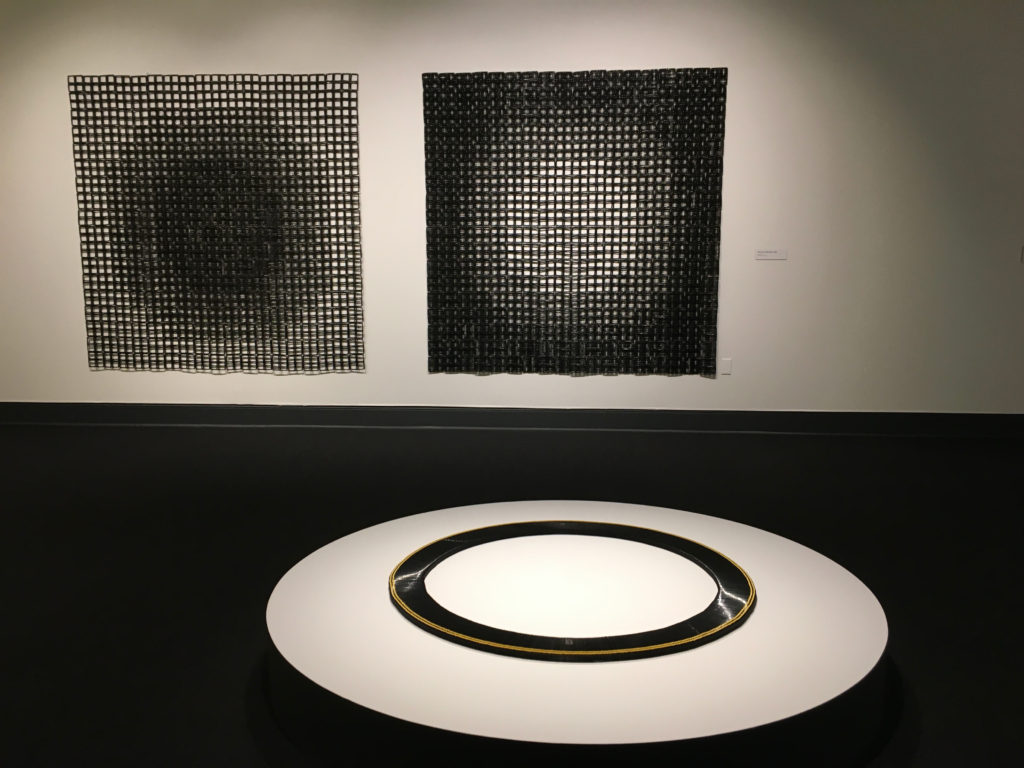

Besides leading socially engaged, participatory exhibitions, Sonya Clark is an active textile and social practice artist. You may have seen her artwork Eye to Eye (2001) featured on the cover of the September 2020 issue of Art Education journal and in the issue’s instructional resource “ written by Penn State Ph.D. candidate and Region 4 member Luke Meeken. An exhibition of her work, “Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend,” is currently at the National Museum of Woman in the Arts. This exhibition delves deep into 100 artworks on race, Blackness, and history. Clark transforms common materials such as sugar, combs, and thread into stunning artworks layered with meaning. Central themes in the exhibition address heritage, labor, language, and visibility, and the galleries are further organized by media, such as combs, hair, and flags. The exhibition closes June 27, so see it soon in person, or check out the online exhibition.

How can we apply current debates and discussions about racial equity and social justice into our art curriculum?

Kristin Baxter, Ed.D. is an Associate Professor of Art and Director of the Art Education Program at Moravian College and member of Region 10 of PAEA. She also continues to teach children, adolescents, and families through her work as a mindfulness and art teacher at Shanti Project.

This spring the YWCA created an online “21-Day Racial Equity and Social Justice Challenge.”

https://www.ywcachallenge.org/session_catalog/#/attendee/B5364140-019C-4D80-82FB-FA101A6EA528/catalog Each day, since, April 19, I’ve received a selection of videos, articles, and podcasts curated around themes such as Reparations for Slavery; Reparations and Indigenous People; Ending the use of Native American Imagery in Sports; Intimate Partner Violence in the LGBTQ+ Community, among others. Like many of you, as I read, watch, listen to, and participate in debates and discussions, I am continually asking myself, how can I continue to build meaningful, robust content around racial equity and social justice in my art classes?

This blog entry describes how I’ve done this through Moravian College’s Town Hall program. I’ll also present ideas and questions that I will take to my classes in the future, that might spark some reflections for you too.

Moravian College hosts an annual Town Hall each spring. The Town Hall is made up of about 10 courses across disciplines, including over 150 students and faculty. When a faculty member agrees to teach a Town Hall course, they include a research project for their students based on one of four annual, academic themes: Healthcare; Sustainability; Poverty and Inequality; War, Peace, and the Just Society.

One of my art education methods courses, called Art Material Investigations: Processes and Structures, was one of the Town Hall courses this spring of 2021. My students researched contemporary artists whose work engages with one of those academic themes. During the virtual, online Town Hall event this past April, my students were placed in breakout rooms according to those academic themes. Each breakout room had roughly ten students from across all of the Town Hall classes, whose research fit within the same theme. Each group also included a faculty moderator and a community member, such as local school leaders, politicians, and business owners. In this way, the Town Hall fosters interdisciplinary discussion and action to solve critical issues for our contemporary world and demonstrates how interconnected many social, political, and economic problems are.

As a culminating part of their research, my students created their own works of art, based on the artists they researched. Through the use of a variety of processes and materials during our course, students also identify which art materials best communicate certain ideas.

One of my students, Janessa Ternosky, researched LaToya Ruby Fraizer, an African American activist and artist, who is well-known for her documentary-style black and white photographs that record the impact of environmental devastation on the health and well-being of marginalized families and communities in the Midwest. Inspired by Frazier’s work, Janessa created her own series of black and white photographs. Janessa explains, “my photo series, A Place Like Home, explores my childhood home and how the town I came from shaped and affected my family as a whole and ourselves individually” (Janessa Ternosky, personal communication, April 27, 2021).

Credit: Janessa Ternosky, Sister, 2021, and Grandpa, 2021 from the series, A Place Like Home. (Photos used with permission).

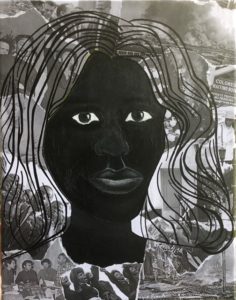

Another student, Ashlynn Forney, researched Kerry James Marshall, whose art references the Civil Rights Movement and addresses the “invisibility of Black people in America and the unnecessarily negative connotations associated with darkness” (Art21, 2021, para. 4). Ashlynn’s mixed media piece, entitled “Impactful Faces” was inspired by Marshall’s mixed media work “Untitled Self-Portrait (Supermodel) from 1994. Ashlynn explains that “a variety of historical photos that display instances of racial injustice, segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and impactful individuals during those moments were strategically places around the painted portrait” (Ashlynn Forney, personal communication, May 2, 2021).

Credit: Ashlynn Forney, Impactful Faces, 2021, mixed media on canvas, 11” x 14.” Inspired by Kerry James Marshall’s work “Untitled Self-Portrait (Supermodel), 1994, mixed media on paper, 1994. (Photo used with permission).

Through participating in the Town Hall and also in the YWCA’s “21-Day Racial Equity and Social Justice Challenge,” I wrestle with questions that I could use to prompt discussion and artmaking in my classes next semester.

Perhaps these reflections might also inspire you to see how issues of racial equity and social justice could impact your teaching too:

- Danielle Bainbridge (2020, December 9), in her video titled The History of Reparations, describes how the City of Chicago paid reparations to victims of Jon Burge, police commander. From the 1970s-1990s, Burge led police officers to torture Black men into giving confessions for crimes they did not commit. Part of the reparations that were part of the settlement included mandatory curriculum in the Chicago public school system about Burge’s crimes. What role do you think public school, PreK-12 education in general, and art education curriculum design in particular, could play in reparations?

- Has your favorite sports team changed its name, mascot, and/or logo because it was originally racist? How were multiple cultural perspectives and organizations involved in choosing the new name? Imagine that you need to create a new name, logo, and mascot for your team, what steps would you take to create these? Who would be involved in the designs? Dr. Anton Treuer (2019, December 13), Professor of Ojibwe and Native American author, argues that we need to have ethics around this issue in sports culture. What role does the study of ethics play in design and art education?

- Amy Graff (2017, August 30), in her article titled, “The next generation of California public school students will skip the ‘mission project’,” she describes how the “fourth-grade tradition of building a California mission out of Popsicle sticks and sugar cubes is being pushed aside by the state as history lessons change to reflect all cultures and more accurately depict the past” (para. 1). In addition to ignoring how the missionaries impacted the Native people in the area, the art project had few meaningful art learning objectives. One parent is quoted in the article as remarking: “I was so relived they didn’t have to build that dumb building (as I did back in 1980) and that they got a fuller picture of life in California at that time” (para. 10). How are art projects that are meant to broaden understanding about cultures actually racist and support stereotypes? If your current art education curriculum includes a culture- or history- based project, how might you reflect on its relevance? Is that project culturally biased or even racist?

- 80% of women and children who have experienced homelessness have also experienced domestic violence (National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017, May 30). Survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault urgently need safe and affordable housing. Have students research the types housing options that should be available in our communities, like emergency shelters, transitional housing, and permanent supportive housing, among others. How could we design an art lesson based on a discussion of housing options within a neighborhood and community? How does the design of a community reflect and support the diverse needs of the people who live there?

References

- Art21. (2021). Kerry James Marshall. Art21. https://art21.org/artist/kerry-james-marshall/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwp86EBhD7ARIsAFkgakh7lCLVi1VYWGsYFiY2XS2KzdTz1d0_QBdzh1zucruwU2rwwyfbHacaAi-REALw_wcB

- Bainbridge, D. (2020, December 9). The History of Reparations. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98u7NNBWsMU&ab_channel=OriginOfEverything

- Graff, A. (2017, August 30), The next generation of California public school students will skip the ‘mission project.’ SFGATE.com. https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/California-public-schools-mission-project-model-11953722.php

- National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. (2017, May 30). The Intersection of Homelessness and Domestic Violence. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVnwGFqyEcQ&ab_channel=NationalResourceCenteronDomesticViolence

- Treuer, A. (2019, December 13). Not Your Mascot: Native Americans and Team Mascots. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orVEuhZsRgo&ab_channel=TPTOriginals

Part I: Capacity Development for the 21st Century

Gaming your Pedagogy:

Taking inspiration from games, toys and play in the art classroom

Renee Jackson is an Assistant Professor and Program Head of Art Education at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, in the Art Education and Community Arts Practices Department at Temple University. She is an artist, critical feminist pedagogue, and scholar, whose research interests relate to the disruption of oppressive mechanisms in education and the integration of game-design and game-play as collaborative art forms and learning tools, in support of this goal. Jackson has worked as an art educator for 21 years at all levels and in various contexts.

Guest Series Introduction: Not Gamification

This blog post is the first of a four-part series that will take place over the summer. I have been drawing inspiration from games and toys in my own teaching for some time. My fascination for such things has existed, not surprisingly, since I was a child. My brother and I developed highly complex narratives for our toys. Our Cabbage Patch Kids, for example, were summoned into the X-world by a giant mouth with giant tongues, that would wrap around them and inhale them through this living portal when they were needed to figure out a problem, solve a mystery, or rescue someone. This series is about taking inspiration from such play, toys and games, and applying it to learning in the art classroom in various ways.

When I say, “taking inspiration from games”, what I don’t mean is gamification. This is a term that has become somewhat popularized over the last 10 years or so. It is a trend wherein generalized gaming principles are transferred to the “real” world (Coniceros, 2013; Kapp, 2012; Liyakasa, 2012; Danforth, 2011; Kho, 2012; Werbach & Johnson, 2012). Though there are many interpretations of what gamification means, and how it can be used within classrooms and the everyday, it is primarily mobilized by incentivizing. The airmiles type awards plans or coffee punch cards for example, are prime examples of the gamification of our everyday lives. This approach is really just another take on behaviorism, reinforcing extrinsic rewards for “good” capitalist behavior, rather than prioritizing intrinsic motivation, accomplishing tasks for one’s own development or joy. In this sense, gamification imitates traditional rote teaching.

What I mean instead, is taking inspiration from games in a variety of innovative ways, that can enrich progressive, student-centered, experiential approaches to learning in the art classroom.

So, through this four-part series, I will share some ideas and strategies that I have used in my own K – 12 classrooms and within community contexts over the years, for integrating games and playful approaches into the art classroom setting, or towards what I have come to refer to as gaming your pedagogy!

The four-part series will cover the following:

- Capacity development for the 21st century

- Game inspired creative processes

- Game and toy informed art projects

- Integrating video games into art curricula

Part I: Capacity Development for the 21st Century

Toys and games play a significant role in learning across cultures. Of particular fascination to me is the Inuit culture of Canada’s North. Learning through play was particularly important when the Inuit people were primarily nomadic into the 70s and 80s (Briggs, 1991). The harsh climate in the Canadian North demanded keen awareness of the physical environment, as well as physical resilience. The collective nature of the nomadic life also required emotional control and attention to detail for survival. The lifestyle demanded both a large degree of improvisation and innovative thinking. Inuit people of all ages could be seen tinkering with objects by taking them apart and experimenting (Briggs, 1991). The game Cat’s Cradle is just one example of a traditional game that encourages innovative thinking. A round of sinew is stretched between the player’s two hands. The participant’s fingers are used to form a series of loops that resembled, for example, animal shapes. The person creating the most shapes which no one can duplicate is the winner. Learning through such games, like much of the learning in art class, is experiential. One learns by doing and develops capacities such as innovation and resourcefulness through particular types of experience. Jean Briggs, an anthropologist who lived with the Inuit for 18 months observed that play was initiated by both children and adults and was “used to set problems for children to solve in order to develop skills and capacities to help them survive physically, emotionally and psychologically, in this highly threatening environment” (Briggs, 1991).

Before moving on to consider games from the perspective of capacity development in relation to our contemporary context, I want to provide a brief and fascinating example of the type of innovative thinking manifested by the Netsilik Inuit. This example comes from a Balikci film from 1968, described by Briggs (1991). The challenge in this particular situation was that there wasn’t any wood available to create dogsled skis when it was time to move camp. To solve this problem, they cut up caribou hide from the summer tent, dampened it, and wrapped it around a line of fish laid head to tail. This was frozen, fastened together with crossbars of caribou antler, lashed with sealskin, and used to replace wooden skis. When the sled eventually thawed in the spring, they ate the fish, sewed the tent back together, and moved in!

If we consider the idea of capacity development for the 21st century within the context of contemporary art education, what are some game-based approaches and strategies that can support the contemporary needs of our students? I want to premise this conceptual exploration by stating that the Inuit people continue to use games in various ways (Canadian Geographic, 2021a), and that my very brief introduction only touches on the complex use of games when Inuit were primarily nomadic, as an entry point to considering games as serious learning tools that can support significant capacity development of children and youth in relation to the demands of their surrounding environment. The question: what capacities, relevant to our contemporary context, can we help to develop and strengthen within our students using game-based approaches? is a point of departure not meant to trivialize the idea of needs and survival, particularly in light of Indigenous people who face ongoing systemic oppression that translates into literal challenges to survival such as access to medical care, clean water, and safe environments (Canadian Geographic, 2021b). I also want to acknowledge that working with our students to understand systemic oppression is an imperative need but will not be the focus of this particular blog post.

Creativity

The idea of playing and tinkering with objects and material remains an important way of developing the creative thinking skills required to be resourceful and adept at problem-solving. Simple challenges in the art classroom can strengthen these capacities on a regular basis. For example, the challenge of receiving a random object and imagining all of the different ways it can be used. What else can a cork or clothes peg become? How else can they be used?

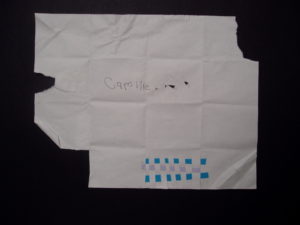

Similarly, when using a new medium for the first time, I have students fold and unfold a scrap piece of paper, dividing it into rectangles. The challenge then is to create as many different types of marks as possible within two minutes. Prior to starting, I invite a student or two to demonstrate creating “two very different marks” in front of the group. One can take the opportunity here to help them realize that creating two different “symbols” for example a heart and a smiley face, are not “very different marks”. These “symbols” are composed of very similar types of gestures/lines. Have another student come up and give it a try until something more innovative takes place and can be highlighted as an exemplar (ie/splatter paint or poke a hole in the paper). This can work for any wet or dry media, as well as collage and paper manipulation. In the example by Camille, she ingeniously spat on and chewed her paper for some interesting texture. For any project, versions of this can take place based on asking ourselves the question: What are the skills required to successfully accomplish this particular task? How can we encourage students to stretch and develop such skills? When it comes to 3d work, for example, found object sculpture, I provide students with random assortments of objects and the challenge becomes “find 3 different ways to attach 2 disparate things together; or find 3 different ways to completely alter the object.” The more ideas one can conjure in relation to these challenges, the further one travels from contrived or stereotypical conclusions, into the realm of innovation. This capacity makes us better problem-solvers as artists and is also transferable to our everyday circumstances. Students are always invited and encouraged to share their discoveries, supporting student-centered learning and collaboration. The infamous “they copied me” statements are discouraged and a culture of credit and appreciation “I learned this from so and so” is encouraged. Such warm-up activities were used in my former K – 12 classrooms, to fuel a wide variety of projects, including some related to games and toys such as: Found Object Toys and Dolls; Diffabilities Dolls; Clothe the Naked Mannequins; Crack the Secret Code; and Story-telling Towers. I will go into further detail about these projects in part 3 of this series.

Attention

In our very distracted society, development of the capacity to pay attention to the world and to detail is important not only to our everyday well-being, but it enables aesthetic appreciation and connects us to our surroundings on a deeper level. More broadly, the capacity to pay attention is key to the development of creative engaged citizens. One cannot ask questions of things they don’t notice, nor celebrate or be critical of a world and of people if they are not capable of paying attention to.

With this in mind, I integrate attention games and exercises into everyday activities. For example, adding something to the classroom, taking something away, or moving something. Try it and you will quickly see that this exercise not only helps to strengthen attention over time, but when first applied truly reveals, to the shock of the students themselves, the degree to which they do not notice things! Another approach to both engage student attention, and simultaneously have help gathering random classroom materials, is the use of what I call “Collector Contraptions” at the elementary level, and “Information Files” at the secondary and post-secondary levels.

The Collector Contraption itself is made in class from found materials and is a place to store the special everyday materials we may typically discard yet can of course repurpose and use in a myriad of ways in the art classroom.

I also often also use scavenger hunts or treasure hunts in various ways. For example, hiding material for a project around the classroom. I often even hid items or materials in plastic eggs. For a grade 10 project titled Textured Fruit of Emotion, the introductory lesson involved the haunted house style approach where students are blindfolded and had to touch all kinds of textures. In this case though, rather than eyeballs and guts, students would similarly touch a variety of textures, but translate this into metaphor – what type of emotion could this texture represent? From here we moved to contour drawings of fruit (another great attention exercise!), and then to translating the contour drawings into 3 dimensions using wire and plyers. This structure was then covered in glue- dipped cheesecloth and texture and color added to tell the story of a particularly intense emotional moment experienced by the student. The stories were recorded, and an installation conceived by the students, of plaster cast hands reaching from the wall holding the fruit was constructed at the entrance of the school, where the recordings were played on a loop (much to the chagrin of the administrative assistant whose desk was near the entrance). Tech note: dowels were attached to the ½ plaster cast hands and holes the size of the dowels were wet-drilled into the concrete wall.

Other simple examples of attention exercises are looking at optical illusions and spot the different games (which can be made by the students).

Community Building

Community building of course is particularly important when, despite the ability to be connected in so many potentially positive ways through technology and social media platforms, cyberbullying, trolling, xenophobia, racism, and toxic work environments, are just a few of our very serious contemporary challenges that can be addressed to some degree, through our efforts towards community building in schools.

The project Community Lucky Charms involved gessoing enough large sticks per student (although this could also take place in groups). Students first covered this stick with symbols that represented them. The game element came into play next, when students were given a piece of string and asked to figure out how to sturdily attach their stick to a partner’s stick. These partners would then join another two partners and work together to join their pairs of sticks. This continued until 2 sturdy stick installations were built (adjustments allowed). Students then created “lucky charms” from found objects/collector contraption items, wire, beads, and string. A tag was attached to this charm with suggestions for how to take care of your community, and then hung from the stick installation. These works were placed around the school building, and when the exhibition was complete, the strings were cut and the sticks and lucky charms became guerilla additions to community gardens, parks, patches of dirt, or home plants or gardens.

The Shape Drawing Game was an introductory exercise to a larger project titled The Neighborhood Transformation Project. Students worked in groups to imagine the ways that they could transform their urban neighborhoods. Answers took many forms of course – a soccer stadium, a zoo, a farm. Each student was given a sticky note with a shape or line drawn on it. The challenge was to draw their idea, with the constraint that they had to work together because each person could draw only the shape or line that they were given. One rule was that no one could draw over top of or add to anyone else’s work without permission. Another was that there was to be no fighting or raising voices, though constructive debate was encouraged. Students were asked to pay particular attention to how they worked together (what rules and strategies did you develop? How did you ensure constructive debate versus destructive fighting? What is the difference?)

Toys, games and play can be incorporated into the art classroom in a variety of ways and can contribute to key capacities that are important to healthy human development in our contemporary context. Stay tuned for my next installment in June: Game inspired creative processes.

References

- Briggs, J.L. (1991). Expecting the Unexpected: Canadian Inuit Training for an Experimental Lifestyle. Ethos, 19 (3), 259 – 287.

- Canadian Geographic. (2021a). Inuit games. Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/games-and-sports/

- Canadian Geographic. (2021b). The road to reconciliation. Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/the-road-to-reconciliation/

- Coniceros, R. (2013). Making workplace safety an engaging game. Business Insurance, 47, 1 – 12.

- CornerStone Staffing. (2021). Distracted walking. https://www.cornerstonestaffing.com/safety-resources/distracted-walking/

- Danforth, L. (2011). Games, Gamers, & Games: Gamification and Libraries. Library Journal, 84.

- Kapp, K.M. (2012). Games, gamification, and the quest for learner engagement. Training & Development, 64 – 68

- Kho, N.D. (2012). Getting Gamified: Publishers score big with online games. Econtent, 20 – 24.

- Liyakasa, K. (2012). Game On! Customer relationship management, 28 – 32.

- Sydney Opthalmic Specialists. (July 11, 2018). Optical illusions behind the scenes. News. https://sosdoctors.com.au/optical-illusions-behind-the-scenes/

- Werbach, K. & Johnson, S. (2012). How to Gamify Smart. BizEd, 52 – 53.

Art & Literacy

Julia L. Hovanec is the Higher Education Division Director for PAEA and has taught art for more than thirty-four years to all age levels. Currently, she teaches Art Education at Kutztown University.

The seamless integration of literacy-based strategies into the art room makes perfect sense for all age levels. This Dynamic Duo can yield amazing results. I have been conducting research on this Commanding Combination for over twenty years. If done correctly, the Beautiful Blend affords students the opportunity to bridge connections between art and life. The literacy-based strategies become the bridge, facilitating the realization of the importance of the visual arts as well as brings to light the many natural connections that exist between art and literacy.

My research began when I volunteered to go into my son’s classroom to teach art. I created portable art lessons based on a picture book. Scranimals by Jack Prelutsky, Painting the Wind by Emily MacLachlan & When Pigasso Met Mootisse by Nina Laden, to name a few. The first time I read a book to his class, I became hooked on using picture books as hooks to introduce substantive visual art lessons. When I had my son’s class outside actually painting the wind, I remember thinking…this is pure magic. I quickly became known as the Book Lady, and I decided that I loved that title. I owned it. I entitled my collection of individual cases of books and lessons, BooksART (my mother came up with that title). Each case contained a picture book, a lesson plan, an example, and many other supplemental materials.

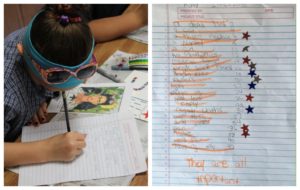

Since then, I have researched many other ways in which to integrate literacy into my own art classes, from elementary school to college. I still am a firm believer in the power of the picture book for all age levels. Yes, I read picture books to my college students. But that is just the tip of the iceberg. I decided to choose my top ten literacy-based strategies to share (I happen to love top ten lists). This was an especially tough list to write as I have employed numerous literacy-based strategies throughout the years. Here it goes…

1. Picture Books as Hooks – using favorite picture books to hook students into learning. Picture books are chockful of universal truths and understandings.

2. Ekphrasis – very simply put…poetically writing about art. It is a Greek word for the description of a work of art produced as a rhetorical exercise, an ekphrastic poem is a vivid, often dramatic, verbal description of a visual work of art.

3. Story Art – writing imaginative stories about works of art, considering what happened before or after or what is going on now. I also like when the students choose a portrait for the character, a landscape for the setting an abstract work of art for the conflict or plot.

4. List Poems – writing a list of everything they can think about that connects to a topic, theme, or work of art. It is an immediate poem. After curating the list and rearranging it, each word or phrase on the list becomes a line in the poem.

5. Word Wall – a collection of words displayed in large visible letters on a wall with pictures. The word wall in an art room can be designed to be an interactive tool for students. It could contain vocabulary used while creating art, talking about art, and reflecting on art. Word walls provide a permanently visible model for high-frequency words while offering students a reference and support when speaking about and writing about art.

6. Word Collage – Pat Mora wrote a poem entitled, Words Free as Confetti. That poem inspired this strategy. Simply, the students collect or wrangle words (check out Lexi the Word Wrangler by Rebecca Van Slyke and The Word Collector by Peter H. Reynolds that inspire them or have some sort of theme or some sort of meaning and then toss them onto a piece of paper like confetti and collage them into a work of art.

7. Picture Writing – based on Beth Olshansky’s work…students begin by creating a picture and then write in response to their art by describing what they see. This strategy treats words and pictures as equals. The picture the student creates inspires the words they write. They write with confidence.

8. Concrete Poetry – a form of poetry and an excellent literacy-based strategy in which poetry and visual arts come together one hundred percent. The poem is the art and the art’s the poem.

9. Artful Quotes – students artfully write their favorite into a work of art. The artful quotes can then be displayed, or they can be pulled together to create an inspirational book.

10. Reading Carpet – creating an ideal space in the art room is such a great idea. The carpet should be a space that is inviting, comfortable, and different from the rest of the room. It features an abundance of books, plenty of works of art, and a basket of artifacts. The space is perfect for individual learning, group learning, and teacher instruction. If a student finishes early or they need some time to think about a lesson before they begin, they can go to the carpet.

My hope is that these ten out of one-thousand and ten strategies spark your curiosity about the Dynamic Duo, Commendanding Combination, and Beautiful Blend of Art & Literacy. If you have any questions or would like more information, please feel free to contact me at hovanec@kutztown.edu.

The Power of Storytelling

Carla Rodrigues is the K-5 Remote Art Teacher for the Easton Area School District where she currently teaches students from all seven elementary schools. Carla shares a personal memoir with a guiding interest in storytelling in the classroom.

In my teenage years, I was convinced that telling stories from the past would hold me back. After all, those were the years I could not wait to leap into the future. Ironically, as I get older and my children grow up and take flight, I find myself telling them stories in an attempt to keep memories alive. Recently, my mother sent me a photograph that captures a family story that I told my children, bringing together some of the bits and pieces they had heard from me before.

It was 1979. I was visiting Brazil with my younger sister Anita and my mother. The paintings around us (see image above) were made by my maternal grandmother. I still remember how the oil paint and turpentine felt almost inebriating. Struggling to sustain a growing family in Portugal on two low-income teaching salaries, my parents started to look for other places where we could live more comfortably. Brazil was one of those places. Nonetheless, we never ended up moving there.

It was 1979. I was visiting Brazil with my younger sister Anita and my mother. The paintings around us (see image above) were made by my maternal grandmother. I still remember how the oil paint and turpentine felt almost inebriating. Struggling to sustain a growing family in Portugal on two low-income teaching salaries, my parents started to look for other places where we could live more comfortably. Brazil was one of those places. Nonetheless, we never ended up moving there.

My grandmother aspired to be a professional artist. Instead of pursuing her passion full-time, she raised her children and grandchildren, attended classes, and painted whenever she could. She had only lived in Brazil for three years. The Angolan Civil War of 1975 forced her to leave behind their farmland and family house that my grandfather built for their family of seven. My grandmother’s paintings were of real and imaginary things, merging old with new dreams, but rarely depicted resentment and sorrow despite her circumstances.

It was during the family’s escape from the war that my mother left her family and went to Portugal. She was newly married to my father and carried me in her womb when they flew to his native land in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the island of São Miguel. I was born and raised rooted in the land, but with my eyes on the horizon of the sea. The desire to explore and add something beautiful and useful to the world remains the same after all these years. I believe this is part of the reason why I currently live in the United States of America and teach Visual Arts to children.

My grandmother is no longer with us. 2020 took her at 96 years old. The stories she told us through her paintings will keep her alive in our memories. I understand now that storytelling takes us back to the past, but it can also propel us into the future, which is now more uncertain than ever. I’m sure that we will be telling COVID-19 related stories for years to come and they won’t be all sad. I heard many stories of hope in the middle of loss and despair during war times and arduous beginnings. Storytelling can help us paint our lives with gratitude and hope. It’s a form of art and an art of many forms.

I see great benefits of incorporating storytelling in Visual Arts instruction, especially in Art History lessons. This year, for example, when learning about Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), before introducing any information about the artist and his art, I provided second-grade students with an image of one of his paintings (Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005). The students were asked to observe the painting very carefully and use its details to develop a short story with a beginning, middle, and end, imagining what could have happened before, during, and after that very moment captured by the artist. Given the digital platform that my students use for virtual learning, they recorded their own voices telling the stories and sharing them with me. I then displayed a painting by Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). When looking at this painting (Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1800-1) and Wiley’s painting, side by side, the students compared and contrasted both paintings and drew conclusions about the relationship between the two. What started with a storytelling exercise evolved into insightful and powerful discussions about subject matter and form, historical and cultural contexts of artwork from different times and places in the world, touching upon a variety of art, literature, history, social science standards while making connections to current events.

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005 (Left) – Jacques-Louis David, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1800-01 (Right).

In another example (pre-COVID), when introducing first-grade students to Abstract Art and its pioneer Wassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944), I played a classical theme from Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840-1893). First, I had the students listen to the music with their eyes closed and imagine it as a sequence of events or a story. Students shared out single words such as peaceful, happy, sad, and scary to describe particular parts of their stories. Together, we matched each word with a color (peaceful/light blue, sad/grey, happy/yellow, scary/dark red). The students then shared their stories with one another as they helped each other with selecting pieces of colored paper that best described their respective stories. As the students listened to the music one more time, they cut out geometric and organic shapes, pasted them on larger pieces of white paper, and added different kinds of black lines over and around the shapes. After a gallery walk, as we listened to the music one last time and commented on each other’s work, I asked, “What if we could actually see sounds?” This set the stage to finally introduce Kandinsky and his artwork, synesthesia, and abstract art. This lesson not only allowed the application of the students’ prior knowledge of shape and line quality, but also enabled them to develop their compositional, art interpretation, collaboration, and communication skills, and make connections between their artwork and the work of Kandinsky in a more authentic way. Since I taught this lesson, a few complementary digital tools have been developed and made available through Google Arts & Culture (https://artsandculture.

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925

Storytelling skills can also be applied to older grades. In fourth and fifth grade, for example, when reflecting on their artwork and writing artist statements, students start by describing their individual creative processes from beginning to end in order to identify the how and why of their work. I often use Georgia O’Keefe as a reference when she wrote, “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else… Nobody really sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time… So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.” In this brief story, O’Keeffe describes her how and why in very simple terms. Have you noticed how naturally students default to storytelling when making connections between their work and a special event in their lives, person, or memory anyway?

I now understand that storytelling helps us make sense of who we are. It establishes our roots so we can rise up even stronger. It uniquely draws our experiences in the sketchbook of life so, as we flip through its pages, we can see a path behind us and feel a sense of direction and purpose ahead of us. Storytelling is personal, so is the art we make. And, every time we tell a story or share our art, we commune with the world.

If you use storytelling in your classroom, I would love to hear from you! You can message me via email at region10@paea.org, Instagram @rodrigues.art.classes, Facebook @mrsrodriguesartclasses, or Twitter @EASDRodrigues.

*Cassidy Kandinsky lesson via collaboration with student-teacher Anna Nestor

Incorporate Creative Mindsets into PPE Exploration

Xue Dong is an Assistant Professor at East Stroudsburg University (ESU) Art + Design department. Xue obtained her MS Degree in the industrial design field at Auburn University. Her teaching responsibilities include 3D design and the product design field. Xue has been a member of NAEA since last year!

The spread of COVID-19 and reopening has placed healthcare providers and the surrounding community at high risk. According to this situation, Professor Darlene Farris-Labar and I worked together to solve the PPE demand problem. The purpose is to reduce employee exposure to hazards and provide a safe and efficient working environment through a collaborative group. By establishing partnerships with Lehigh Valley Health Network and local makers around the area, ESU was able to mass-produce face shields and stethoscopes over the past few months, at a much faster rate. Our contribution has been featured in IDSA (Industrial Design Society of America) Membership Spotlight, CHANNEL 16 NEWS WNEP, and Pocono Records Newspapers.

Even though our 3d printed face shield design has made a breakthrough in helping those on the frontlines, we still would like to exam other needs of the medical community. We have involved students in redesigning medical equipment funded by ESU 2020 S.U.R.E grant and “Out of the Box Grant”.

These grants allowed three students to work with PPE solutions such as enhancing voice face mask “Bee Head” face shield and Lip-read” mask to respond to the new reopen challenges, while simultaneously providing an educational and experiential component. We incorporated creative mindsets and social responsibilities throughout the whole project. Finally, the team has developed and manufactured reliable and functional PPE solutions for the whole community. Through participating in this project, students were able to apply expertise in product design, digital fabrication techniques, as well as entrepreneurship strategies to the real-world scenario. As in addition, there is also further investigation in sustainability, safety, survey, and mass production. Their work has been featured in the College of Central Florida Webber Gallery’s “Masks and Makers.” Exhibition.

To continue to meet the ongoing and dynamic needs for PPE, as the vital and manufacturing hub, ESU’s 3D Printing Super Lab would like to have continuing conversations and opportunities among memberships of PAEA, art professionals, and students. We hope this project will establish a perfect foundation as an on-going subject among interdisciplinary opportunities for the art educators, students, healthcare professionals, and community.

PPE Explorations of ESU Students

PPE Explorations Team

“Bee Head” Face Shield and “Read-lip” Mask

#MuseumFromHome: Digital Engagement at The Andy Warhol Museum

Nicole Dezelon is the Associate Director of Learning at The Andy Warhol Museum, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and was named the PAEA 2019 Outstanding Museum Art Educator. Since 2005, she has spearheaded an array of innovative school partnerships, digital engagement initiatives, and professional development programs at The Warhol.

The Andy Warhol Museum’s Learning and Public Engagement department rapidly adapted our on-site programming by pivoting to online learning and digital engagement during the COVID-19 closures back in March of 2020. We quickly realized the benefits of remote learning such as:

- reaching a global audience

- not being limited by the physical real estate of the studio, classroom, or galleries

- and being able to take full advantage of our museum’s collection and archives instead of being limited by what is currently on view.

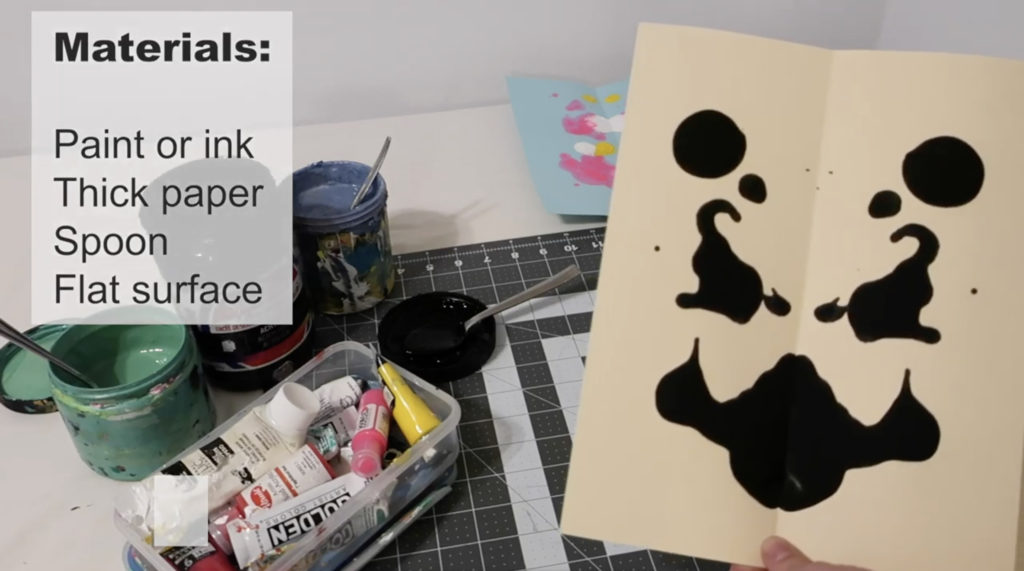

Our first rapid response to the museum’s closure was our MakingIt video series. It was our way of maintaining Warhol’s relevancy while sustaining engagement with our audiences. By adapting Warhol’s artistic processes and techniques using common, household materials, we were able to reach students, families, and makers of all ages virtually from the comfort of home. Our MakingIt video series is available on YouTube and has been a huge success, we were even shortlisted by Kids in Museums for the Best International Digital Activity Family Friendly Museum From Home award.

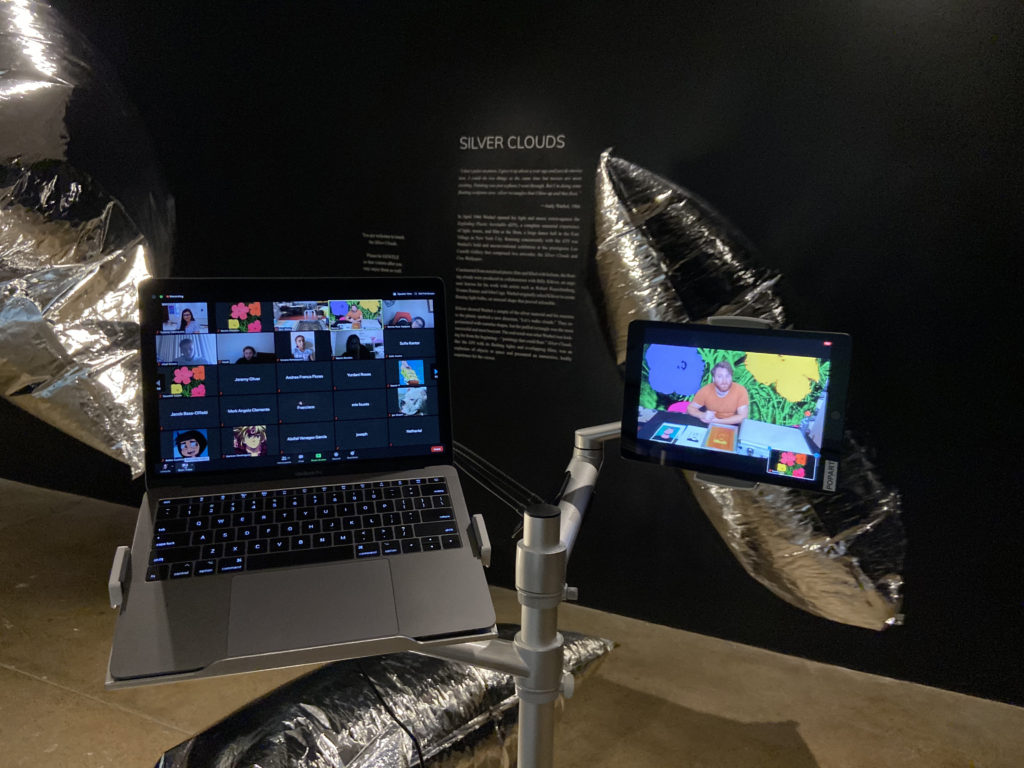

Our second response was the launch of our virtual tour offerings. Through live videoconferencing, participants can discuss works of art in our galleries, watch presentations, and participate in live art-making activities while sharing in two-way conversations with museum educators. We’ve tailored many of our online lessons exploring Warhol’s life, artistic practice, and legacy for a virtual experience and we’ve been tailoring our virtual experiences for groups based on their unique needs. From Pop Art to silkscreen printing, virtual tours can easily be scheduled online and scholarships are available for schools demonstrating need.

Although The Warhol is now open to the public through timed ticketing, we remain committed to our virtual audiences through digital engagement and online learning. As we collectively learn to “navigate the new normal”, we count on educators like you to help make our museum programming better, so we hope that you will visit us virtually, field test our online lessons and resources, and try one of the various artmaking techniques in our MakingIt video series on YouTube.

Virtual Field Trips

Liesl Mahoney is the Associate Educator for School and Family Programs at the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Liesl has a passion for instilling a love of art and museums in children of all ages.

Every year, the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania welcomes thousands of students through its doors to explore the galleries. Trained enthusiastic docents lead the students around the Museum in small groups, stopping to look at artwork that fits with the tour theme chosen by the teacher. Students leave with a greater connection to the artwork and to the surrounding landscape of the beautiful Brandywine Valley.

Photo Taken by Mark Gormel

This has been the norm the entire time I have worked at Brandywine. Then suddenly, in early March, I found myself in the tough position of calling teachers who had booked tours and telling them that their visit was canceled. Everyone was very understanding, but one thing I heard from multiple teachers was “I hope we can still do something with your Museum in some sort of capacity.”

It was from that statement that the Museum’s Virtual Field Trips were born. We wanted the virtual experiences to have some of the elements of our in-person tours, and so we created them to be thematic and targeted for various age groups. We wanted to make things as easy as we could for teachers, therefore we pre-recorded the videos and made them available for streaming both in the classroom and on individual devices. Teachers can also choose to add a live Zoom feature for students to interact with staff from the Museum. To make these Virtual Field Trips accessible to everyone, they are being offered for free. We did not want cost to be a factor for schools and students during this time.

We were also very cognizant of timing, both for what teachers may want included and what students can handle. For instance, the Animal Safari for Kindergarten through second grade is a fun and interactive tour that takes students on a virtual exploration of selected animal works from the collection in around five minutes. As the grade level increases, so does the level of the content and the overall length of the pre-recorded videos.

Jamie Wyeth, Portrait of Pig; 1970

This new format gives us the potential to reach many new students. Students who have never been to Chadds Ford – and whose school may be too far away for a comfortable field trip commute in person – are able to be transported virtually to the Museum to see what we have to offer. Another exciting factor is that we are no longer confined to viewing only what is currently hanging in the galleries. Now, any artwork in the collection can be part of a Virtual Field Trip, which makes the tours new and fresh even for returning visitors.

I look forward to working with teachers to tailor the Museum’s offerings to their needs. We plan to keep adding to our list of offerings and welcome suggestions. For more information on the tours head to our website https://www.brandywine.org/museum/tours-groups/virtual-school-programs. Feel free to contact me, Liesl Mahoney, at lmahoney@brandywine.org or call me at 610.212.3663.

Connecting with STEAM

Jihan is a Philadelphia visual artist, community arts educator and a museum educator at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Thomas extends her creative work in community centers, shelters, and traditional K-12 classrooms within the Philadelphia School District. Jihan loves being creative and encouraging others in their pathways towards their own unique expressions

This time has truly been challenging for everyone. As a visual artist and community educator, I usually look forward to my summer schedule where I facilitate art programming for campers from all over the city, but like everyone around the world, COVID-19 has completely changed that. Fortunately, I had the wonderful opportunity to participate as a STEAM instructor for Greater Work Preschool in Philadelphia where the facility operated a small camp through social distancing.

Together, the campers and I learned through STEAM-based projects. One of my favorite projects was when we learned about animal habitats and campers created their own habitat. Campers did a great job identifying the importance of animals being in their natural surroundings. Another great theme focused on engineering where campers learned to construct their own homes. We had the opportunity of exploring the basic elements on how to construct a home as well as draw architectural blue-prints of their own type of home. Along the way, campers made great observations and made meaningful connections with their work. Be sure to check out these great STEAM projects!

NAEA Position Statement on STEAM Education

For more STEAM resources, visit Edutopia.

D5 Creation

D5 Creation