art teacher

now browsing by tag

Highlighting the Positive of Covid Lesson Planning: Finding the Convergence of Content and SEL

Blog post written by Region 11 Representative, Holly Meade

Holly Meade is a Middle School Visual Arts teacher at Downingtown Middle School. She has a BFA, M.Ed in Childhood Development, and additional certifications in ESL and SEL. Region 11 PAEA rep

I am currently teaching virtually, predicted to soon to be hybrid, but anticipating anything can happen and probably will, going back with 2-days notice, wearing a hazmat suit to class, anything. I counted the amount of times I heard the word fluid during a zoom meeting, 9. Fluid is the new moist, the word is dead to me now, a Covid vocabulary casualty, joining unprecedented. As an attendance check-in, I asked my students to describe 2020 in one word, here are some responses: canceled, oof, oop, crazy, disaster, worst (most popular answer), exhausting, my personal favorite… dumpster-fire (I let that slide as one word), luckily no one used unprecedented. Whatever word you choose to describe what’s going on right now, it’s stressful and become more important than ever that we create a space that’s welcoming, supportive, and safe. An environment where content connects rigor and engagement with social and emotional learning (SEL). A meaningful convergence.

Art teachers are naturals at creating projects which spark joy, are hands-on, engage students authentically and our lesson design process naturally fits into the UbD format. Many school districts are imparting SEL into advisory blocks or guidance department lead lessons, but how do make this sustainable and creatively connect the SEL and content in an authentic way.

You can build upon what your district or individual school has been spotlighting or reinforce it. Many schools are focusing on self-management which is regulating emotions and managing stress. I examined my curriculum and lessons that I would be doing if we were in person and adjusted the content to converge with SEL domains that were not already being covered by school mandated lessons, like stress management. On a side note, I’m not managing my stress well, so I didn’t feel this was a skill I could model at this moment. I do not see recreating lessons as additional work, I see it as an opportunity to examine what is important to creating a safe supportive space that supports social and emotional learning while not sacrificing content or rigor. The examination gave me the opportunity to work SEL into the content lessons in a meaningful way. For example, when reflecting upon the dumpster fire (now one word) that is happening around us. I looked at my own children and how they were feeling powerless and without a meaningful voice. This prompted me to recreate a unit called Artists and Identity and add Voice to the mix. I found it manageable to re-create my content by highlighting just 2 of the 5 SEL domains, self-awareness, and social awareness. Because of the change in teaching format to virtual, I had to recreate how I am delivering content anyway, and when (if) we return to in-person learning, who knows what sharing supplies will look like, so it is great timing for an update. Yes, I found one positive in 2020 lesson planning. Using essential questions that tie emotions with content is another way to practice and model SEL skills while building connections.

Art is empowering. Teaching and modeling how artists use their voice for change and to highlight social issues has been amazing. We are making connections of voice and historical context using Dorothea Lange to the NBA uniforms and the work of a local artist, Russell Craig. I wish I had always given them more opportunity for discussion! We often underestimate how much our students are paying attention to the events of the world and their ability to talk about it. But like Mr. Rodgers said, “Anything human is mentionable and anything mentionable is manageable.” Taking time to create a safe, supportive space is essential for building an environment where students can connect and discuss challenging feelings, which teaches, models, and gives students an opportunity to practice SEL skills like empathy. We do need to evaluate our environments and do everything with compassion. Not just in Covid class, always in our class.

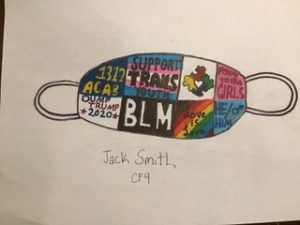

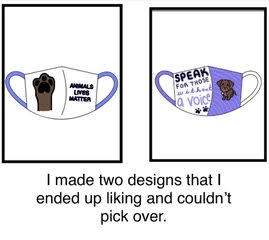

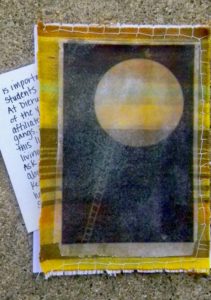

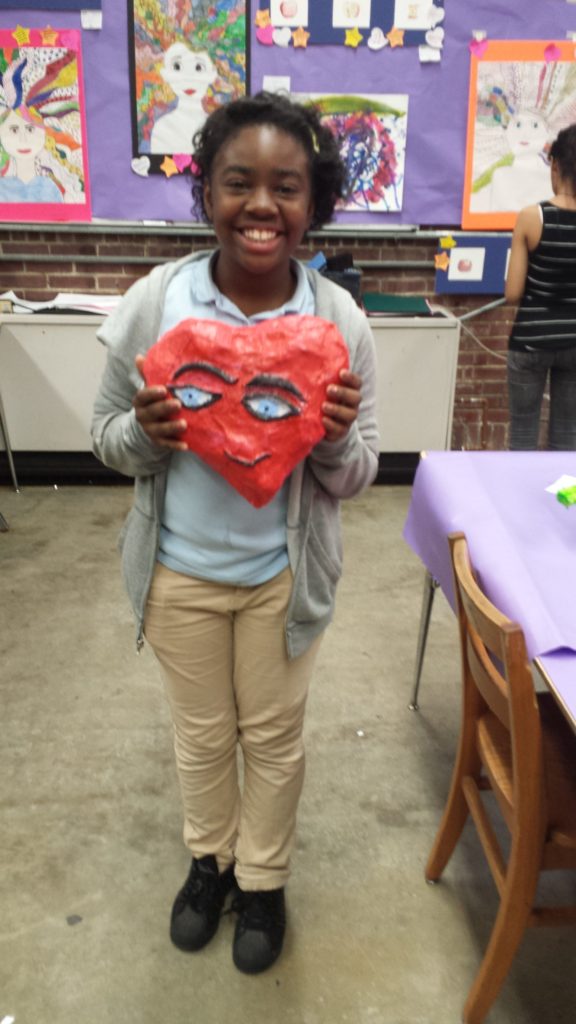

Intro design project building voice, identity, and empathy by letting others see our voice and letting someone else into your world

Embracing the chaos with the Comcast technician 20 minutes before hosting virtual Back-to-School Night

Creating Connections in the Virtual Art Classroom

Blog Entry By Leslie C. Sotomayor

Art empowers us to interconnect through diversified ways of thinking and creating meaning for our humanity and communities. Art facilitates creative ways for engagement and navigating difficult issues, emotions, and well being. How can we reimagine the arts towards social change in different ways through art education and virtual worlds? As I reflect in the midst of so much chaos in the U.S. with a pandemic and an increase of social unrest, I believe we are in an opportune time as artists and educators to create meaningful change and disrupt the traditional troupes of what art education is and can be.

As I taught for the sixth summer with the Upward Bound Program it was a very different experience via a virtual realm with no physical studio space. I had to develop ways to create a meaningful curriculum for students in the arts that was interdisciplinary and accessible. All of the students were afforded an art box with basic art materials and a laptop with a camera for virtual meetings. I decided to center my curriculum on the work of Puerto Rican artist Soraida Martinez http://www.soraida.com and the theorizing she coined titled verdadism. Verdad is the Spanish word for truth and ism is the suffix that means the theorizing of an idea or concept. Martinez’s theorizing and work stems from a place of grappling with her own identity and history as a woman of color who did not fit into any one category neatly and grew tired of underrepresented artwork in the United States being diminished and undervalued within the art world. She chose to challenge and resist traditional norms in the art world by creating her own genre of work. Martinez confronted the racist and sexist social issues and microaggressions she experienced and witnessed as she paints abstract images and activates a new language for herself through verdadism. Martinez paints and juxtaposes her paintings with a title and text that is showcased together to contextualize the art pieces and position her art into the world in the way in which she deems necessary addressing social and everyday issues as a Puerto Rican woman. Martinez developed this style to stand in her truth and theorize about her art in ways that are meaningful to her, from the inside out.

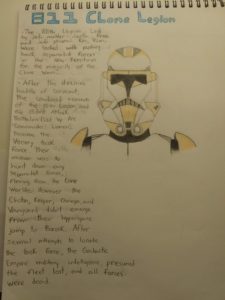

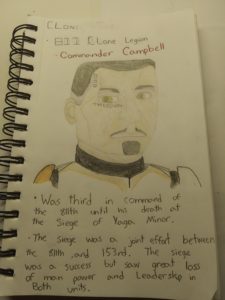

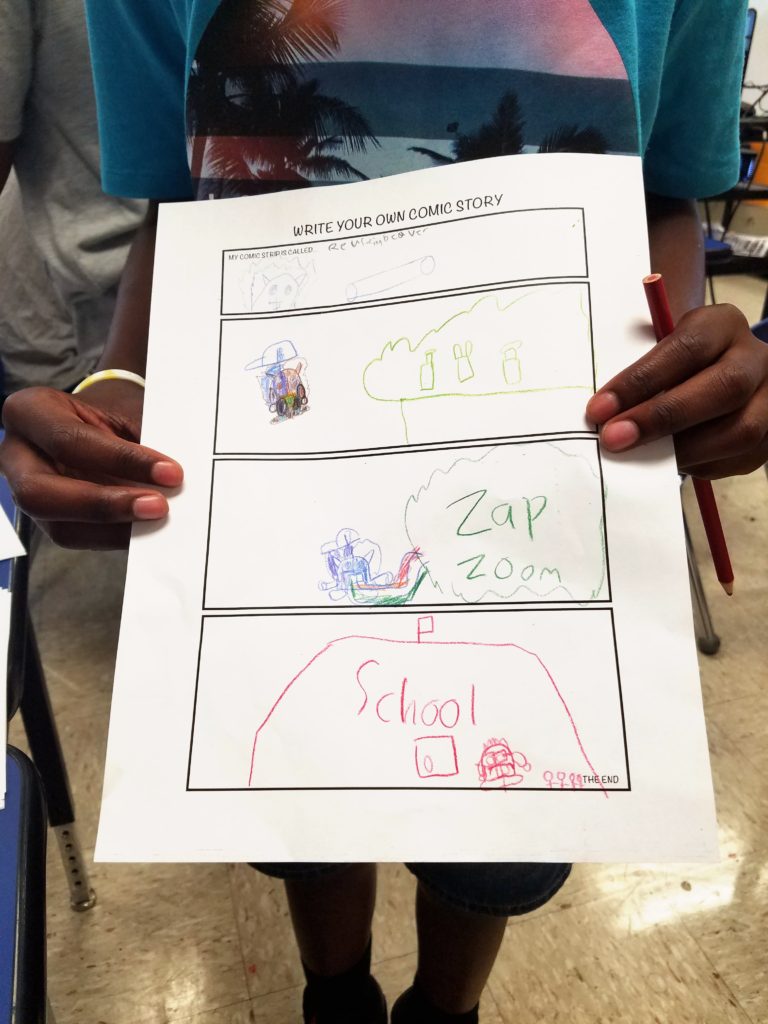

As I introduced Upward Bound high school students to the work of Soraida Martinez I layered the idea of art and language with improvisations for curious art-making. What I mean by this is a simple yet often overlooked component of being intentional about meeting each student where they are in their creative process and allow for that point to serve as a place for engagement and creative processes. For example, one student created a symbol around a concept for an initiative that was sparked by the Star Wars movie series. He created meaning with his symbology in the design and color palette theorizing about who would use the symbol and why in his imagined team for social justice (see image 1). I share here various examples of student’s artwork in a variety of ways all done via virtual teaching, discussions, and documentation of creative processes (see images 2 and 3 below). What I have learned throughout this process is that meaningful connections through virtual spaces are more than possible and offer new ways of thinking and implementing new forms of knowledge production in art education.

High School student created a motif symbol of a team initiative as a new branch of Star Wars with a storyline (theorizing) about the history and initiative creating a team defending social justice.

Another student combined her interest in digital photography and poetry by writing a series of three poems, translated into Spanish, and taking photos in her house of staged scenes and editing the photographs on her laptop.

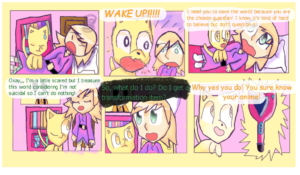

Another Student created a graphic novel in English and together we translated the graphic novel into Spanish for bilingual readers. See more here: https://twitter.com/hashtag/TransformacionesClubdeGatos?src=hashtag_click

Leslie Sotomayor received a Dual PhD in Art Education and Women’s Studies in 2020. She is an Assistant Professor in Art Education at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania.

I’ve been teaching for a while now . . .what’s next?

I’ve been teaching for a while now . . .what’s next?

Discovering what opportunities exist for Art Educators when considering Master’s Programs.

So you have been teaching for a while now and you are considering what is next? For many of us, teaching is a way of life, and seeking ways to better our practice is simply intuitive. But deciding the best way to acquire that learning and what those extra steps will do in the long run can be difficult to answer. My name is Ben Hoffman and I am the Visual Arts Teacher at Kutztown Area High School. Since graduating from Kutztown University in 2015, my journey has taken me to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and back. I have been incredibly fortunate to teach and work in museum settings, galleries, community arts centers, summer arts programs, and public-school settings. In addition to my range of experiences in teaching, I currently serve as the PAEA Region10 Representative as well as chairman of the Kutztown University Arts Society.

As an Art Educator, you are equipped with far many more talents and experiences than what our certification deems. Teaching K-12 is merely one of the many rewarding opportunities that we have available. This past year, I successfully completed my fourth year at Kutztown Area High School as well as graduated with my Master’s in Art Education from Kutztown University. For many of us, working towards our Master’s in Education is often most appropriate and considered an acceptable pathway when pursuing our Level II Certification. Unlike my undergrad experience, the courses in my Master’s program were directly driven to my pedagogy and helped enrich the quality of my program. Much of any undergraduate program is directed towards the understanding of pedagogy and curriculum while my time as a graduate student applied that theory to practice. From rewriting curriculum, developing new courses, embodying a new mindset for teaching, and advocating for our growing program, my experience as a graduate student was unbelievable.

Regardless of the path that you may take, it goes without saying that it will take time and energy. I was highly motivated to learn just as much as I wanted to move up on the pay scale. But just recently, I stood at the crossroads of no school and yearning that desire to continue to grow. This is when I then contemplated other master’s programs and even my doctorate. Now that I have my Master’s In Art Education, what more can I do?

Connecting with people and establishing those relationships is the foundational piece to making any impact. Now having my Masters in Art Education, I am considered qualified to teach in non-traditional settings, serve as a nonprofit program director or even an instructional designer. Each of these professions seemed equally interesting, but I still wanted to know what more was available. This is when I stumbled upon a Master of Arts in Arts Administration. Unlike the education world, Arts Administration extends opportunities to individuals who are equally as dedicated, talented, and passionate as the artists and audiences they support.

The nonprofit arts sector generates nearly $170 billion in economic activity each year according to the America for the Arts economic impact study. Because of this economic and political impact, the public sector, arts, and cultural organizations are increasingly seeking trained professionals to provide vision and leadership. (Kutztown University, 2019) While teaching is one of the most rewarding fields there is the experiences that could be acquired from such a unique program that sparked my interest and felt applicable to the events our district puts on. I saw this opportunity as the key to my success in being able to learn and value the connection I share as an artist, educator, and advocate. Whether coordinating large-scale festivals, serving as a museum or gallery director or simply coordinating community events, this was the next step in my journey as an art educator.

Often a master’s program can feel daunting and overwhelming, but from my own experiences, that deep investigation of the arts and its cultural impact throughout time and across cultures have significantly impacted the person that I am today. Since graduating with my Master’s in Art Education, the excitement to grow as an educator has equally fueled my artistic practice and understanding of leadership. Furthermore, having that deepened understanding of our roots in history has helped shaped my appreciation for our field and the impact we continue to make. I would be remised to look back and appreciate all that every art educator has done to pave the groundwork for my future.

While I begin my second Master’s, I continue to question all things and continue to seek the most meaningful connections for my own classroom. While writing papers and reflecting may seem like much of any graduate program, the conversations between like-minded peers in the field are incredibly valuable. Furthermore, serving as Chairman of the Kutztown University Arts Society has challenged my own best practices and demanded that I view the Arts from a unique perspective. While teaching comes with its own set of principles and expectations, leading a group of professionals who each come with a diverse set of experiences and skills has its challenges. It is those difference and range of perspectives that cultivate a healthy and successful arts organization. It is incredibly interesting to see how my perspectives as a teacher are often valued in these new settings when working alongside those in higher education.

It is never an easy decision to make when picking a program. Every district will have different procedures and should be considered when selecting a program. I am incredibly fortunate that my district values teachers to continue their education. While loans and time may be a burden, know that there are countless opportunities and ways in which you can tailor the best program for you. I was determined to finish in three years. For others in the program, there was a range of flexibility. Some students were those who decided later in life to pursue their master’s while some students had transitioned directly from their undergraduate program full-time.

Regardless of the path that you may decide or the timeline you establish for yourself, know that you will never regret the experience. Any graduate program you choose will demand that you set aside time to work and reflect, but just as you now actively participate in PAEA, you will have no problem in accomplishing this goal. For many, just like myself, you may never know where the Arts will take you, but as long as the Arts are alive and healthy, there will be nothing but success in your future. Every story will be different. I am incredibly grateful for my experience as a graduate student and look forward to my time as an Arts Administration student.

I hope that my story inspires you to take that next step in whatever your journey has in store for you. No matter the path, the Arts will always be there as will PAEA to support you in all professional development endeavors. If you should have any questions, comments, or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact me directly. I am more than happy to extend my knowledge and support each of you in the best ways that I can. Thank you again.

Respectfully,

Benjamin E. Hoffman

Kutztown Area High School

Visual Arts Teacher

bhoffman@kasd.org

Anew Coming into View

Blog Post by:

Carrie Nordlund, PhD

Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Another year is coming into view and we too are ceaselessly in a state of becoming (Unrath & Nordlund, 2009). The term epiphany is a Greek derivative meaning to come into view (McDonald, 2008). Some new year’s resolutions come into view from epiphanies, profound illuminations of experiences with subsequent and emergent crystalizing moments of self-identity (Nordlund, 2019). As we usher in a new year, we can revisit the crystalizing moments we have cherished and open ourselves to what may come further into view. We may also recall challenges as we attribute meaning to the past year, those paralyzing moments of the past. Yet, these too offer us opportunities to recommit our efforts in becoming our best selves. The new year brings into view potentiality, to become anew.

The new year can pose uncertainty. One way to take in hand the feelings associated with uncertainty is to start to recognize epiphanies, with their consequential understandings of our deeply held certainties and feelings about self and the world, often ensue after periods of inner turmoil including states of anxiety and depression (Denzen, 1989, 1990; Jensen, 1999; McDonald, 2008; Miller, W.R. & C’de Baca, 2001; Pyne, 2014). Jarvis (1997) defined epiphany as “sudden discontinuous change, leading to profound, positive, and enduring transformation through reconfiguration of an individual’s most deeply held beliefs about self and the world” (p. v). When we are called to deeply feel and consider, we have reconfiguration available to us to see and be anew.

How might we arrive at reconfiguration in the new year? To follow, I offer some strategies affording reflection and reconfiguration. In the past, I have facilitated these three strategies for and with K-12 students, preservice art educators and myself via action research aimed at working on being the best self I can be.

My Personal Art History

The first strategy, “My Personal Art History”, offers a means to consider how might we better recognize our relationship with art and if necessary, reconfigure our aesthetic code during the new year.

Carrie Miller, Artist Educator, North Schuylkill Elementary School

Identities are constructed artifacts. We tend to teach from what we know. Our past experiences with art and art education partly construct our present and future beliefs about art and art pedagogy. What journey brought you to the creating artist and becoming teacher you are today? What is your personal art story?

Reflect on your child and adult art story, aesthetic experiences of the past and blossoming abilities in and with art. Visually describe any crystallizing and paralyzing moments during your explorations with art. Recreate in a timeline of visual expressions and metaphors of this art history starting from your earliest memories to now, 2020. The timeline leads to you to defining a future aesthetic code.

Postcard Moments

The second strategy, “Postcard Moments”, offers a means to consider sudden, turning point moments of epiphanies that provoke transformation of our conventions (Miller & C’de Baca, 2001; Nordlund 2019; Unrath & Nordlund, 2009).

Amanda Madea, Community School Coordinator, Bethlehem School District

Postcard Moments are small postcard-sized expressions created at self-determined key moments. The visual metaphors express a moment of sudden enlightenment—an epiphany—accompanied by written narrative about the personal “aha” and journey to it. The small postcard format serves as a compact, portable, and focused place where these such reflections are actualized, just as a traveler might choose which external event or experience from a trip is significant enough to write home.

Postcard Moments can become a larger culminating artifact by juxtaposing and synthesizing individual epiphanal works from the journey (e.g. journey book, travel game, visual mapping, digital film, photomontage,…). “Ahas” along the way or during the journey, lead to enduring understandings relevant to the traveler’s transformation or the potentiality of transformation and are characterized by traveler’s comprehension of the intimately interconnected parts of something complex. Postcard Moments often provide acute awareness of vistas previously unseen (Nordlund, 2019).

Personal Improvement Plan

The third strategy, “Personal Improvement Plan”*, offers a means to design an action plan in the new year targeting a specific goal to become one’s best self.

Carrie Nordlund, Associate Professor of Art Education, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Visual Artifact from Steiner’s Six Steps in Self-development Exercises

What threatens or impedes you from being your best self? To engage in a Personal Improvement Plan (PIP), take on a self-designed project that helps you become your best self over the new year. Intentionally choose a condition or disposition that is lesser and needs to be made more significant, positive, and enduring by ascribing personal meaning to it through a plan of improvement. Allow yourself to be vulnerable to create a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-based) goal as the core of your improvement plan.

My PIP goal typically starts as a wondering, such as “What might occur when I devotedly practice mindfulness exercises directed at educators?” To answer this question, my PIP plan entailed an autoethnography study over six months where I sequentially employed and maintained Rudolf Steiner’s (1910/2011) Six Steps in Self-development: The Supplementary Exercises for Teachers by implementing one exercise each month until all six were engaged in the sixth month. I discovered and described in narratives the deep meaning or essence of experiencing the phenomena of Steiner’s six supplemental exercises entitled (1) control of thoughts; (2) initiative of will; (3) equanimity; (4) positivity; (5) open-mindedness; and (6) equilibrium. The outcome narratives explicated the phenomena under investigation and became a means for intervention, i.e., action research on my own practices and state of being.

When you employ a Personal Improvement Plan consider weekly documentation of your progress, including dates and times, pictures, successes, failures, outcomes, notes, wonderings, insights, and implications. Feelings of doubt, immobility, or disconfirmation can be or lead to breakthroughs. Personal improvement plans can either target our individual best selves, or on a macro level, us as change agents for a global best self.

*The “Personal Improvement Plan” was created and championed by Dr. Peg Speirs, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania.

References

Jensen, K. L. (1999). Lesbian epiphanies: Women coming out later in life. Harrington Park Press, New York.

McDonald, M. G. (2008). The nature of epiphanic experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(1), 89–115.

Miller, W.R. & C’de Baca, J. (2001). Quantum change: When epiphanies and sudden insights transform ordinary lives. Guilford, New York.

Nordlund, C. (2019). Letters to colleagues: A community of practice for navigating and reshaping identity. In Daichendt (Ed.), Visual Inquiry: Learning and Teaching Art, 8(1), 49–62.

Pyne, S. (2014). The role of experience in the iterative development of the Lake Huron treaty atlas. In Fraser Taylor, D.R. (Ed.), Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography: Applications and Indigenous Mapping, 2nd Edition (pp. 245 -259). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science.

Steiner, R. (2011). Six steps in self-development: The supplementary exercise. Rudolf Steiner Press.

Unrath, K. & Nordlund, C. (2009). Postcard moments: Significant moments in teaching art”. In Dhillon, P. (Ed.), Visual Arts Research, 35(1), 91–105.

D5 Creation

D5 Creation